“The nature of moral judgments,” Susan Sontag wrote, “depends on our capacity for paying attention.” A lot of horrors seem to compete for our attention these days, from Trump’s temper tantrums which are destabilizing the world’s economy and security, to the burning of the Amazon, which is undermining its climate. So, if I choose to attend to my home town, Oberlin, Ohio, and the college where I spent the last 33 years, it’s not because it is the most important of the many issues that demand our consideration, but because, in its own small way, examining events here can offer some insights on the moment we are living.

The students have begun to repopulate the town after a summer spent near and far. (There is no summer session at the College.) The sports teams are the first to return; my days of working out in a nearly empty gym are coming to an end. The first-years arrive in a few days, to be followed soon after by all the others. For the most part, they have been absent as the Gibson’s issue played out in a nearby Lorain County court room as well as in hundreds, if not thousands, of news reports, commentaries, and social media streams. Unlike most of those, and similar to my commentaries from earlier in the summer (here and here), I am more interested in exploring some broad contextual themes that can help us understand the terrain on which “Gibson’s” is playing out and not re-litigating the events themselves, including the trial.

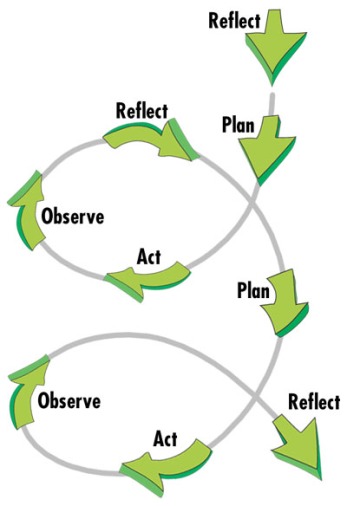

The Action-Reflection Cycle

Let me begin with a useful piece of pedagogical advice known as the action-reflection cycle. The cycle begins with thinking (theorizing) about what you want to accomplish by any action (say, what you hope students will learn in a particular class). Based on that, you plan a strategy for action (your lesson plan), put the plan into action (teach), observe and consider the results (via various assessment mechanisms), and then determine whether, in actual practice, you were able to achieve the outcomes you hoped for. If you didn’t, you need to modify the strategy, rethink the theory, rewrite the lesson plans, and try again, try better.

There’s a lot to be gained by applying the action-reflection cycle to the “Gibson’s affair,” my shorthand way of referring to the series of events that began shortly after the November 2016 election with a shoplifting incident and a student protest against what they at the time perceived to be an attack on a Black student by a local merchant – it would, of course, prove more complex. All this led, nearly three years later, to a jury verdict awarding a massive sum to the plaintiffs, the Gibsons. Despite the fact that the legal wheels are still turning, the moment is ripe for some reflection. And, if many points remain in dispute, perhaps we can agree on a few, and see them as starting points for the next action-reflection cycle.

- The jury’s verdict in the Gibson’s case has produced a disastrous outcome for the College and its students, those who engaged in the protests as well as the far larger number of students who didn’t. It has caused and will continue to cause financial and reputational damage to the College without advancing the student protesters’ implicit goals. The events haven’t helped us think about, or respond to, race and racism in our town, surely the protesters’ central goal. Because what happened does not appear to be the outcome that the protesters, the student body, or the College wanted, it would be more than warranted for everyone to reflect on the actions that were taken and, more importantly, ask what they would do differently in the future, what needs to change to arrive at a better outcome. In my opinion (which others might not share), this shouldn’t involve retreating from deeply held principles or from the social justice goals that, along with academic and artistic excellence, have long been a part of Oberlin’s “peculiar” tradition, but rather finding better ways to advance them.

- The jury’s verdict has also produced a troubling outcome for the town. It has soured town-gown relations, historically uneasy, as many studies have shown. Gibson’s v. Oberlin now snakes through the town like a live electrical wire: touch it at your own peril. Some merchants have declared their establishments “Gibson’s-free zones,” where no talk of the controversy is allowed. Hundreds of incoming students, as well as faculty of color, recently received hateful and threatening emails from an unknown source. Because these are outcomes that (hopefully) few would celebrate, it is important that those who live and work in town and would wish for a different outcome now reflect on what happened and on what we need to do to help the healing process. This is not a question of “loyalties,” of how one views the events or the outcome of the jury trial. It is a question of how we reach for deeper understandings of the ways in which our actions impact human well-being, how we can find better ways of living together.

- Finally, this is, I believe, the moment to draw a line under one activity that needs to stop: shoplifting from local merchants. College administrators need to establish clear deterrents which can be written into the College’s Honor Code and the rules and regulations governing student behavior. Oberlin should make it clear that students found guilty of shoplifting will be placed on probation and that repeat offenders will be suspended. As with all aspects of the Honor Code, adding this should offer a teachable moment, encouraging students to reflect on their own role in improving town-gown relations.

A recent critique of the College’s actions in the “Gibson’s affair” quoted John J. Shipherd, one of Oberlin’s 19th century founders, who observed that “Oberlin is peculiar in that which is good,” and then refers to a more contemporary inversion of Shipherd, one that implies that the college is now seen as being “good in that which is peculiar.” I would suggest that “eccentric” is a more appropriate term than “peculiar,” agreeing with J.S. Mill (On Liberty) that “precisely because the tyranny of opinion is such as to make eccentricity a reproach, it is desirable, in order to break through that tyranny, that people should be eccentric.” Still, it is useful to explore, however briefly, why Oberlin, the college, is seen by the “outside world,” including Lorain County, as “peculiar” in the first sense. This is particularly important as the reputation of the college often depends more on how it is seen than on what it actually does.

Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Tells Your Story

On November 6, 2015, an article by Clover Linh Tran appeared the Oberlin Review under the title, “CDS Appropriates Asian Dishes, Students Say.” In it, a College junior from Japan, Tomoyo Joshi, is quoted as saying, “When you’re cooking a country’s dish for other people, including ones who have never tried the original dish before, you’re also representing the meaning of the dish as well as its culture. So,” she concluded, “if people not from that heritage take food, modify it and serve it as ‘authentic,’ it is appropriative.” If a shoplifting incident set off the “Gibson’s affair,” this statement sparked the “banh mi affair,” an incident, leading to a labeling of the College that continues to shape the way many who “don’t know the original” (and some who do) have come to view it. The “banh mi” affair has not only been used to ridicule the College, but has been employed as an example in the contention that a “radicalized 5 or 10 percent” of students determines “the tone for the entire institution.” This reasoning has been repeated in explaining other events at the College, leading up to and including the Gibson’s protest. In “condescending” to these radical students, the charge implies, the College continues to “betray its finest traditions, and make itself a national laughingstock.”

An employee makes a roll at Dascomb Dining Hall’s sushi bar. Oberlin Review, Nov. 6, 2015 (Bryan Rubin, Photo Editor)

So let’s explore how a dining hall complaint turned Oberlin into “a national laughingstock,” and who, to borrow from Hamilton, is telling Oberlin’s story. It just might suggest something about how others, maybe even Lorain County jurors, think about the College.

In the Oberlin Review’s article, the author reports on conversations with six students, five of whom were from Asian countries; the sixth was Asian-American. Three of the students quoted were critical of the “Asian Dishes” served and mentioned that others were, as well; one had no problem with the food; and two didn’t comment on the food but instead recommended ways in which conversations between CDS (Campus Dining Services) and the students might be used to avoid further conflicts. As one of the latter students argued, “We — including myself — can always learn more about how to admit that we don’t know everything about every culture in the world and have a ‘We’re still trying to learn more’ kind of attitude.” In short, hers was the kind of response one would hope to hear from any college student, whether at Oberlin or elsewhere.

Not surprisingly, the Review had reported on food issues at Oberlin many times before, but none of those articles raised any national eyebrows. A commentary about a Diwali meal served in the dining hall (“On my third Diwali at Oberlin, I had one of the best Campus Dining Services dinners in my three years on campus”) somehow didn’t make it into the New York Time’s Wednesday food section, nor did reports of Kosher Passover meals being more widely available capture the attention of the Jerusalem Post. All that reportage stayed where most campus writing remains: on campus.

Not so for the issue of “cultural appropriation” (a term, one should note, that was raised in the offending article only once, and only by one student). Six weeks after the Review article, a story ridiculing Oberlin appeared in the New York Post, Rupert Murdoch’s right-wing tabloid boasting the 4th largest circulation in the United States. The article appeared under the headline, “Students at Lena Dunham’s College Offended by Lack of Fried Chicken.” Not quite as historic as the Daily New’s “Ford to City: Drop Dead,” but catchy, nonetheless. The chance to skewer the “gastronomically correct students at Oberlin College” and throw in alumna Lena Dunham to boot was too good to pass up. Still, who is going to bother with an article six weeks past its sell-by date?

Not so for the issue of “cultural appropriation” (a term, one should note, that was raised in the offending article only once, and only by one student). Six weeks after the Review article, a story ridiculing Oberlin appeared in the New York Post, Rupert Murdoch’s right-wing tabloid boasting the 4th largest circulation in the United States. The article appeared under the headline, “Students at Lena Dunham’s College Offended by Lack of Fried Chicken.” Not quite as historic as the Daily New’s “Ford to City: Drop Dead,” but catchy, nonetheless. The chance to skewer the “gastronomically correct students at Oberlin College” and throw in alumna Lena Dunham to boot was too good to pass up. Still, who is going to bother with an article six weeks past its sell-by date?

As it turns out, everybody. The story was picked up by Newsweek two days later (Dec. 20) and then quickly found its way to the New York Times (Dec. 21: “Oberlin Students Take Culture War to the Dining Hall”) and the Washington Post (“Oberlin College Sushi ‘Disrespectful’ of Japanese”). From there, it sprinted to The Atlantic, The Daily Beast, The Wall Street Journal, Tablet, The Chronicle of Higher Education, Campus Reform, and dozens of others. One could read of Oberlin’s culinary contretemps in The Orange County (CA) Register as well as The Santa Fe New Mexican. Nor did it stop at the water’s edge. The Jerusalem Post picked it up on January 18, 2016, and the story was covered in The Independent (UK) (highlighting “undercooked sushi”), The Telegraph (UK), the Korea Times (South Korea – I haven’t been able to peruse the North Korean press), and the NZ Herald (New Zealand!), which didn’t get the scoop until July 24, 2016. It must have arrived by boat. Maybe one could escape this onslaught by avoiding the news and just sticking to sports? Not really: “247Sports” carried it, as did “Inside Hoops.” Was there nowhere to hide? Apparently not, since it popped up in Seventeen as well as Vanity Fair. And don’t even talk to me about “Breitbart” (“Campus Crazies at Oberlin…”) or The Federalist Papers.

And if you think the media’s reputation-crushing onslaught would draw to a close when everyone was tired of General Tso and had more worry about with General Trump, think again. The New York Times returned to it in two articles in 2019, and (liberal) Nicholas Kristof referenced it in his comments on the Gibson’s case as an example of how “knee-jerk liberalism” damages its own cause. The Washington Post reprised the story on May 12 and June 2, 2017, and again in its Gibson’s coverage on June 19, 2019. The recent Commentary critique, written by a former colleague (and friend), finds in the food affair yet another example in which the “radicalized few” set the tone for the college as a whole. “[S]tudents protested ‘cultural appropriation’ in the dining hall,” he observes. “The banh mi sandwich was made with soggy ciabatta not a crispy baguette, General Tso’s chicken was steamed not fried, and so on.”

The Banh Mi Effect

So, let’s recap: An article written in a local campus newspaper reporting on complaints by three students (and balanced by the quite measured comments of three others), was picked up six weeks later, weaponized (add Lena Dunham and remove any reasonable comments), and sent out into the world by a right-wing tabloid where it was picked up by, seemingly, every media outlet on God’s green earth, only to return, time and again, as an example of Oberlin’s privileged, radical, preposterous students.

But, why retrace the banh mi debacle here? In part, to answer the charge that it is “the radicalized 5 or 10 percent of the population [that] establishes the tone for the entire institution,” whereas, quite often, it is others who are telling our story, most often in ways that don’t come close to representing the College accurately. Deep within the on-going culture wars, in the age of the internet where no comment, however small or unrepresentative, won’t find its way into somebody’s outrage machine, we should be cautious about suggesting that the institution has fallen under the thrall of a small number of “radicalized students” when, often, it is those outside of the College (both conservative and liberal, it would seem) who have made those “radicalized students,” – those three who complained about the dining hall’s preparation of ethnic food – its voice. Is it any wonder that the College comes to be viewed with mild wonderment, as if animals at a zoo, suspicion, or disdain?

Of course, the banh mi effect is not the whole story, nor would I argue that it is. I trace the history of this story not to whine about poor Oberlin’s media coverage, but to observe that this is the world which we inhabit, like it or not. And yet it’s not one that we are required to promote by re-circulating the false images that it generates. Our story is literally being written by others, often in ways that are deeply problematic, and that have serious consequences not just for Oberlin, but for other colleges and universities targeted by reactionary activists. (Why the liberal press often eats this up is beyond my remit.) Attention is required when an organization like Turning Point USA, an ultra-conservative student group that encourages its members to report faculty who espouse “liberal” ideas in class, offered a workshop at its recent conference (addressed by no less than Trump, himself) titled “Suing Your School 101.” I’ve said this before: this is about more than Oberlin.

A Pew Research Center poll released a few days ago confirms the already noticeable partisan division on the importance of higher education. From 2015 to 2019, the share among Republicans saying colleges have a negative effect on the country jumped from 37% to 59%. That is a monumental shift in only 4 years. But why is higher education so reviled in the eyes of Republican voters, particularly when they are aware of the fact that those with college degrees will do much better economically than those lacking a degree? Obviously, there are many reasons, including rising costs and admissions scandals. But, added to these, according to a study in The Atlantic, is the fact that the “Conservative media has focused heavily on campus protests, free-speech clashes, and debates over…whether offering ethnic food in dining halls constitutes cultural appropriation.” Who knew that comments by three Oberlin students could influence the entire Republican electorate? (As for speech issues, recent research by Georgetown University’s “Free Speech Project” found that the “free-speech clashes” on college campuses in the last few years were directed against both conservative and progressive speakers and, in any case, the 60-some cases represented about 1% of all institutions of higher education in the country. And yet “free speech” on campus, which has drawn the President’s attention, has become one of the Right’s most frequent complaints about higher education in general.)

The challenge of the “banh mi effect” is how one separates issues ginned up in the outside world and made to represent the College, from issues that actually require our consideration. College officials never proposed, nor should they have even considered, censoring the original Review article, wary of what (in fact) came to pass. (Liberty University officials often have done exactly that, with no outcry in the conservative press.) Nor should administrators police student statements, snipping out anything they think might cause offense anywhere from Lorain to New Zealand. On the other hand, cultural appropriation, the issue at the heart of the story, is complex and serious and actually perfect for discussion on college and university campuses, including Oberlin’s. And so it can become an issue for reflection if the faculty feel they are unable to promote and develop the kinds of reasoned and reasoning discussions in class that can help illuminate complex matters such as those presented by cultural appropriation.

Similarly for the Gibson’s affair. I don’t believe that the actions of the students in protesting Gibson’s were well thought out (acting in the heat of the moment rarely produces reasoned responses), and they certainly didn’t produce the kind of results they might have hoped for. But if the College has issues to deal with – and it does – these should not be centered on how to “control” a small number of “radicalized” students. The issues Oberlin needs to deal with are those that arise if the faculty find that they cannot carry out the tasks of teaching and learning in the most productive ways, if they cannot discuss certain topics in class – whether race and racism, the role of activism, or the nature of protest. The issues we need to address are those that come about if faculty feel that students are not raising in class the difficult questions they are capable of raising, not taking the risks with their arguments that they should be taking. But we should also understand when we are being “banh mi-ed,” and not abandon long-standing, mission-driven, progressive (and certainly academic) goals, turn against student activists, or forsake our historic commitment to social justice. Action-reflection: Correct and revise those actions that don’t advance your goals, but don’t give up the goals, certainly not in the face of those who will only be satisfied if Oberlin stops being (in the Millsian sense) “eccentric.”

The Many Views of Reality

If the heart of Gibson’s v. Oberlin was whether the College or the students acted as the “libelous speaker” (and I continue to believe strongly that the jury found incorrectly on that score), the heart of the student protest was based on whether Gibson’s had a “racist history” or whether the actions of Allyn Gibson in confronting the shoplifter were motivated by racial animus (the students charged in the case would concede in a plea deal that they weren’t). In a recent New Yorker article, Kelefa Sanneh writes of the contemporary “crusade against racism.” “It is a fierce movement,” he observes, “and sometimes a frivolous one, aiming the power of its outrage at excessive prison sentences, tasteless Halloween costumes, and many offenses in between.” Whether the students’ protest against Gibson’s was “fierce” or “frivolous,” in my opinion, and as noted above, it not only failed to advance the discussion of an issue that has been a concern in Oberlin (town and College) for a very long time, but made such conversations quite a bit harder. (On the latter point, I recommend Gary Kornblith and Carol Lasser’s recently published, magisterial study, Elusive Utopia: The Struggle for Racial Equality in Oberlin, OH.)

One central aspect of the discussion of race and racism is rooted in the different lived experiences of whites and people of color, particularly African Americans, in this country. It also happens to be an issue severely critiqued in the previously mentioned Commentary article. In it, the author, Abe Socher suggests that Oberlin’s president, Carmen Ambar, brushed away the “guilty pleas, allocutions, and an exhaustive six-week civil trial” to imply that the matter of racial profiling still wasn’t closed. “In interviews,” he continues, “Ambar has hit on a bit of bad philosophy to obfuscate this point. ‘You can have two different lived experiences, and both those things can be true,’ she told the Wall Street Journal editorial board.” Socher concludes by remarking, “One is tempted to say that the facile relativism of this—there is a Gibson truth and an Aladin [the Black student shoplifter] truth; a townie truth and a college truth—reveals the sophistry behind Oberlin’s self-destructive approach…”

When we are talking about race in America (and in Oberlin) – and that is precisely what we are talking about – there can be two (or more) truths, and to ignore this is to ignore history. What is true for a Black motorist and what is true for a white policeman, history has shown and continues to show, can be different but, to each, no less true. What a Black high school student carrying a backpack feels on entering a store in Oberlin, including Gibson’s, or just about anywhere else in the United States, and what the store owner feels on observing that young man, may be quite different, but no less true for each. This is neither facile relativism nor sophistry. It is a product, as President Ambar states, of the “different lived experiences” that have marked Black and white lives in this country for 400 years. Justice Sonia Sotomayor was making the same point in a 2001 lecture, when she said, “I would hope that a wise Latina woman with the richness of her experiences would more often than not reach a better conclusion than a white male who hasn’t lived that life.”

Juries are required to select a single “truth” in deciding a case; they cannot argue that both sides contain some truth. But they, too – as was made explicit in the famous Batson decision, by which prosecutors were prevented from excluding jurors solely on the basis of race – are products of their own histories and lived experiences. We, however, are not a jury looking to settle a case on the basis of one “truth,” one verdict. We are a town and a College that has before us some difficult tasks requiring reflection and revision if we are to heal. In that process, we must be aware of how different lived experiences shape our worlds, as well as being aware of our moral and empathetic obligations to each other. We will move forward if we pay attention, as Sontag recommended, to those issues that demand our consideration, while quieting the outside voices that would be happy to see the College sink back into the swamp that was once the Western Reserve. That, we cannot, and will not, let happen.

There was a passing reference to a Banh-Mi type affair on Netflix’s “Dear White People,” Season1.

LikeLike

Thanks for this very thoughtful piece, Steve.

To my mind, your most important point is: “The issues Oberlin needs to deal with are those that arise if the faculty find that they cannot carry out the tasks of teaching and learning in the most productive ways, if they cannot discuss certain topics in class – whether race and racism, the role of activism, or the nature of protest. The issues we need to address are those that come about if faculty feel that students are not raising in class the difficult questions they are capable of raising, not taking the risks with their arguments that they should be taking.”

As for your point about “relativism”, I know what you’re trying to say; of course people look at things differently. But I am still a modernist: under it all, there is a single reality, and it’s our job to dig that out and help our students to do so. For me, that’s the necessary next step forward based on your argument — as you said in the passage a quoted above. If we don’t, then the postmodern view that there really are different realities will take over, as we are seeing (especially from the likes of Trump, Conway and Giuliani).

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment; let me clarify along the lines that you are suggesting. There is only one set of “facts” and one “reality.” If I punch you in the nose and you hit me back and each of us says that the other started it, there is only one “reality” there, whether or not we are able to agree on it absent a video of the incident. [Ted Chiang deals with this a lot in his short stories.] Regardless of whether we can agree, one person did actually hit the other first, and no amount of reference to outside context will change that (although it might indicate WHY I hit you). When I talk of two “truths,” it is in the context of lived experiences that inform how we perceive the world and our reality. And, as I pointed out above, a Black teenager walking into most stores will perceive probably quite correctly a specific “truth,” i.e., that he will be more suspected of being a shoplifter than the white 50-year old woman who walks in at the same time. This “truth” is based on a long history of “lived experiences.” That is what, I believe, Carmen meant when she said that “You can have two different lived experiences, and both those things can be true,” I think we are in agreement, but thanks for raising the point.

LikeLike

Professor Volk,

Thank you for your wide-ranging post and insightful comments. I especially appreciate your, and Marc’s, thoughts on reality vs relativism. A reaction: I’m not sure that truth or “truths” is the best way and best label for thinking about this topic. Consider:

Within a week OC football will take the field against K College. Former players from both schools are in attendance. Early in the game the Kalamazoo QB throws a clearly incomplete pass. In the Kalamazoo stands we hear different expressions of what just happened From a former offensive lineman, “the pass was way overthrown, the QB missed an open receiver.” But, a former QB says, “the line didn’t hold; the quarterback didn’t have a chance.” An old pass catcher notices the sun in the receiver’s eyes-impossible to see the ball. Another cites the bad play calling, “I could see that play would never work.”

On the Oberlin side there are different impressions of what just happened. A former defensive lineman says the pass rush made the play. A defensive back saw great pass coverage, while last year’s punter says the Oberlin kick, last series, set up the play. Bad field position caused the incompletion. And a former Obie coach, saw a great defensive scheme in front of him. .

All above saw the same reality but all saw it differently. What was most important for each was also different for each but not always in conflict. Wouldn’t it be more accurate to say these were differences in perception or differences in interpretation of reality? More accurate than referring to truths or “truths”? This is the stuff of social science inquiry, especially psychology. Perhaps there is insight from these areas that best frame how we characterize what we experience. This is important. Everyday we, as citizens, need to sort out what is reality in the public sphere we inhabit.

Bill Keller

OC ’63

LikeLike

Thanks for your comments, Bill. The “comment” section of a blog is probably not the best place to pursue the extremely important issues of what is “truth,” the relationship between “truth” and “interpretation,” and the difference between “truth” and “fact.” And I’d enjoy following up further, perhaps in person or a different forum. But, since we’re here, I’d just say the following: In terms of your analogy, the “fact” of the matter is that the pass was incomplete. That the two teams “interpreted” why it was incomplete differently, is to be expected. That Hillary lost the election is a “fact;” why she lost is the subject of dozens of books and thousands of articles. That the crowd at Trump’s inauguration was smaller than that at Obama’s is a “fact;” that Trump sees it differently is a product of, well, you answer that. Trump lies continuously; in a colloquial fashion, we say that he’s “not telling the truth.” But the matter of “truth” (or, perhaps it would help if I write, “Truth”) is a bigger one, and I tend to see it in the context of “We hold these truths to be self-evident…” In other words, it expresses the larger “certainties” of a particular culture, one that represents power, among other things. (If I have to bring in Foucault, I’d quote him here: “in any given culture and at any given moment, there is always only one episteme that defines the conditions of possibility of all knowledge, whether expressed in a theory or silently invested in a practice.”) Among the “self-evident” truths in the Declaration of Independence are those with which I am in full agreement (“all ‘men’ are created equal”) and those with which I don’t (“endowed by their Creator”). The point I’m making — probably way too simply — is that “truths” (“Truths”) express knowledge/epistemologies (not just interpretation), that the commanding “truth” of a given culture may encourage white shop owners (or Black, for that matter — racism is often internalized) to view young Black shoppers one way. As with Marc, I think we agree in substance — there are “facts” in the world, you can’t make them up, the pass was incomplete; how we talk about larger knowledge systems, what I call “truths,” is a separate matter. It would be easier if we all just agreed to call “facts” “truth,” but I think we lose some important distinctions in the process. Again, thanks for your comments, and “Go Yeo!” –

LikeLike

Thank you Professor Volk for your time and thoughts. We agree on the substance. I understand the lesson behind the situation of shoplifting and race. The consideration of Truth as an overarching concept is one I hadn’t fully absorbed.

Re: two different lived experiences and both true. My conclusion: On the simplest level the experiences are true by definition. It’s true that was the experience. That’s trivial but it may be what was expressed by the association. On a meaningful level, two different experiences may have internalized accurate understandings of reality (both lived experiences are true), inaccurate understanding (lessons may be false), accurate in general but not always specifically, accurate in part but not totally, and likely other combinations. In other words, individual’s may be right, or may be wrong, with the “truths” they live by. This is where objectivity enters, where we look behind the “truth” expressed to discern its validity, to discern the reality. This too seems simple and obvious but I’m not sure things are always so looked at or so expressed.

Bill Keller

OC ’63

LikeLike

I spent the day laying in my hammock reading the trial transcript (yea I know, great social life). It’s devastating. . . Several observations:

* It was repeated throughout the trial that this case was not about the students, but about the administration. The jury received explicit instructions to consider just the behaviors of staff.

* This case was not about free speech, but about libel.

* The jury award did not, as you say, damage Oberlin College. The actions of Krislov, Raimondo, Reed and Jones damaged Oberlin College. The jury award just confirmed the facts.

You say there can be “two or more truths” and that can certainly be so. A lot of Title IX investigations boil down to She Said/He Said where we are left guessing. However, in Gibson’s v. Oberlin we have lots of evidence: emails, texts, eyewitnesses. As I came to the end, it was easy to see why the jury was unanimous. And at $25 million you got off lite.

As you may know, the process of restorative justice requires the perpetrator to take full ownership of their crime. For Oberlin to restore its reputation, the college must first fully admit to the wrong it did to the Gibsons and the community. Yet I see nothing of the sort coming from Anbar.

For the students, we could help them immensely with a campus-wide reading on the Salem Witch Trials. Let them consider the toxic effects of a culture where it only takes hysterical accusations to destroy someone (and recall there was ZERO evidence at trial that Gibson’s was or is racist in any manner). Perhaps it will lead the students to reflect upon their own actions.

But what of the administration? Well, for a start Raimondo, Reed and Jones have to go. As the evidence showed,, their unprofessional and reckless behavior revealed a toxic organizational culture. No, don’t frog march them out of the office in front of cameras. Instead.offer a nice little severance if they decide to “spend more time with the family”. Help them find a new gig someplace far away. At minimum west of the Mississippi.

But in the end, the only way for Oberlin College to survive this crisis is for the students, faculty, staff and alumni to have an open and honest conversation rooted in the facts presented to the jury.

LikeLike

Professor Volk,

Based on your reflection, what actions did the students, faculty, administration, and town take that turned out to be counter-productive, and what actions should each take in the future to arrive at better outcomes?

The deterrent you believe should be written into the Honor Code to stop shoplifting—should it include a provision that the College supports the prosecution of any student caught stealing from local merchants?

Jim Loesel ’63

LikeLike

You don’t ask easy questions, James. I’ll try some quick, but not complete, responses. Hindsight, of course, is 20/20 and I have to remind people that the time in which critical steps could have been taken, between the shoplifting incident/arrests and the protest, was only a few hours, i.e., not really time for faculty or others to have stepped in. But, I’ll take your question at face value. What actions were counterproductive: (1) On the part of the students: while their rush to protest can be understandable given their understanding AT THAT TIME that a Black student had been roughed up and arrested [again, that was their perception at the time], it was counter-productive. Let’s take the claim that Gibson’s was “racist” (I use quotes only to suggest the complexity of the charge). If that were the case, students should have been able to mobilize local residents who, if they felt the charges were warranted, might have joined them. That would have taken time, and suggested to the students whether they were acting alone or with wider support. They probably would have learned a lot by waiting. Students would also have been better served if they turned their questions and protest towards the police, rather than Gibson’s, since questions were raised about how the police handled the affair. (2) On the part of the faculty – all one could say is that, as far as I can tell, faculty weren’t involved, and they probably should have been. Not necessarily in the hours between the arrests and the protest — since that would have been impossible, but in the days after, intervening to ask questions, supporting students in their demand for answers, but also working with them to try to clarify issues. (3) Administrators: Again, hindsight might suggest that College officials shouldn’t have been at the protest in any capacity, although had something gotten out of hand one could easily see the charge raised as to why weren’t College officials there to make sure that everything was safe? It’s harder for me to comment on the Administration’s actions after the events and whether compromises could have been reached that didn’t require the College answering either affirmatively or negatively a question over which it had no competence: Was Gibson’s racist? Probably the College would have been wise to ask for the intervention of local leaders of the faith-based community or other civic leaders to help them mediate – but there are many legal issues here about which I have no competence. (4) Town: I would say that it was counter-productive for Gibson’s to ask the College to come out with a statement that it, Gibson’s, wasn’t racist. As I suggested above, this is not something that the “College” should be making statements about in any direction. As with my point above, I would think that the town, particularly its faith-based leaders (of both Black and white churches) and civic leaders (both Black and white) could have intervened to help resolve this issue, and if I would say that it was counter-productive for the College not to have sought outside mediation, that would apply equally to the Gibsons. But I doubt that anyone really knew the direction in which this was headed.

As for your second question, as I’ve written, yes, I think that an anti-shoplifting statement should be part of the Honor Code. I’m rethinking the question of punishment on the College side for shoplifting, having only recently begun to research the question of “crime and punishment” on college campuses, and issue that has gotten a lot of attention in the Title IX context; I’ll probably weigh in on this question later. But I would certainly say that the College should make it clear that it won’t intervene in any direction in shoplifting prosecutions.

Again, your questions are good ones and serious. We all continue to think about the proper answers.

LikeLike

Professor Volk,

Thank you for your thoughtful reply. I would still be interested in your reflection about how to move forward, i.e., what actions should each take in the future to arrive at better outcomes?

Jim Loesel ’63

LikeLike

You continue to ask hard questions, Jim. I expect no less from an Obie! Again, my answer here will be short and much more needs to be thought about, but I’ve already previewed some of my thinking on these points. (1) Students – in general, they need to think about their goals and whether their proposed steps are likely to get to the desired results. In this, they would be wise to consult with others who they both trust and are likely to raise difficult questions. Hopefully, they would find those trusted voices among the faculty. (2) Faculty – should take more seriously their responsibilities for the “wholeness” of our students, rather than feeling that “Student Life” is in charge of anything outside of instruction. By that, simply, I mean that we need to foster a better sense of of discussion, reason, and deliberation in all our classrooms. (See my post here for more on that: https://steven-volk.blog/2019/07/23/where-does-democratic-engagement-fit-on-your-syllabus/). (3) Administration – When conflicts involve the town, it should equally have available trusted voices with whom it can consult, particularly those likely to raise difficult questions. Students should continue to be supported but they are also mostly over 18 and so need to take responsibility for their own actions. Administrators should make clear what actions (e.g. shoplifting) are not acceptable and should encourage — as it is currently doing — stronger and more positive interactions between students and the town. It also would help to have more opportunities for College and town to engage in communal events. The “Big Parade” in early May was a great addition; others which encourage town participation would be welcome. (4) Town – same advice as with the students and the Administration: seek trusted voices with whom to consult. Understand that the College and the town depend on each other, and that litigation will not serve the ultimate goal of protecting each/both. As tempting as it is, try to avoid indicting the entire College for the actions (as ill-considered as they may be) of a small number of students. Use faith-based and civic organizations to help town-gown dialogues.

LikeLike

No, Professor Volk, I was just lobbing questions back at you that were implicit in your blog comments. It is easy for those of us who live outside Oberlin to make pronouncements about what should be done, but I recognize that it is not that easy for someone like you who lives in Oberlin and whose comments are read by the local community and can be used against you in your regular social interactions by both friends and critics. Whether I agree with you or not, I commend you for a) producing a nearly monthly blog, b) writing with intelligence and thoughtfulness, c) opening your blog to comments, d) maintaining composure when faced with hostile comments, e) and responding promptly to the comments.

That being said, let me reflect further about your comments before I respond with my own ideas.

Jim Loesel ’63

LikeLike

It was only three or four hours between the time the handful of students who witnessed the detention and arrest of the three black students in Tappan Square returned to campus and an email announcing the boycott was sent to VP Raimondo at 11:00 pm. As Professor Volk noted, decisions made in haste and in anger are unlikely to succeed.

A boycott is a major political weapon that is very difficult to wield successfully by pros, let alone amateurs. If, at an early stage in considering what response was appropriate, the organizers considered that a boycott was a possible choice, it would have been prudent to consult a community organizer about how to proceed. A knowledgeable faculty member would have been a good second choice. At the very least they should have gone online to look at available information about organizing a boycott.

With very little effort I found an excellent site with detailed analysis of a variety of political actions including demonstrations https://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/advocacy/direct-action/public-demonstrations/main and boycotts https://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/advocacy/direct-action/organize-boycott/main. Several of Professor Volk’s points about shortcomings of the student efforts are included there. These chapters outline detailed and complex steps you need to go through to have a good chance of succeeding with a demonstration or a boycott. You begin by doing your homework, including gathering the facts. The initial actions seek cooperation, not confrontation. There is a ladder of possible actions until you reach a boycott. By the standards of these models for demonstrations and boycotts, the student efforts not only fell far short of adequate preparation but seem to be a case study of what will go wrong if you proceed without careful planning. In my opinion, some of the actions of VP Raimondo at the demonstration were directed at overcoming the poor student preparation prior to the event.

Perhaps some faculty members and staff had sufficient time to advise the students of the problems they were likely to face with the goals and tactics that had been decided upon—reports place some faculty members as well as staff at the demonstration—but the main responsibility for the failure rests with the students. I hoped that Oberlin would have imparted to its students a greater ability to gather information, analyze, and rationally decide on an appropriate course of action. However, I looked at the Politics curriculum to see if there was a course that might have prepared the would-be social justice warriors for this situation. I found nothing. It seems to me that if Oberlin is to celebrate its unique, eccentric, or peculiar aspect to a liberal education, it should at least give interested students a set of tools to approach social justice actions with competence. If there had been a cadre of students that had taken such a course—let’s call it Social Justice Toolkit 101—perhaps there would have been a better chance of one or more students with appropriate skills could have put the student planning on a productive course instead of the disaster that ensued.

Jim Loesel ’63

LikeLike

You are bound and determined to fuzz it up. You continue to attack the verdict, which was manifestly correct and which followed the letter of the law as it concerns libel.

You present a thoroughly useless “action-reaction cycle” diagram that only an out of touch professor could respect.

You call this “a question of how we reach for deeper understandings of the ways in which our actions impact human well-being, how we can find better ways of living together,” in fact the real questions should center on Oberlin’s arrogance then, and its ongoing arrogance now.

You dive into “cultural appropriation” in a school cafeteria, calling it “complex and serious and actually perfect for discussion on college and university campuses, including Oberlin’s,” when in fact it was never anything more than lunch.

Honest to God, could you possibly be any further out of touch? Your sophistry borders on hilarious, and in fact would be hilarious in a comedy sketch. But you appear to actually mean it, which is even funnier, but also profoundly sad.

This will hurt Oberlin and its students? I have to say: Good, I hope it does. This is one of the purer examples of obnoxious self-entitlement on the part of a pampered elite that I’ve seen in quite some time. I hope parents are taking a hard look at the situation, and sending their kids elsewhere.

Oberlin would be best off with a top-to-bottom housecleaning. Fire all the administrators and most of the faculty. Make it plain to current and future students that the jig is up, and there will be no more of this pathetic, ongoing exercise in self-parody.

This was only the latest train wreck, but it’ll be remembered in the same way that the 1896 “Crash at Crush” is remembered: as an exercise in pointless and foolish destruction. Oberlin had better shape up, and shape up fast, or there just not be much of an Oberlin left.

LikeLike

Pingback: Reputation | After Class

My husband and I spent some time last night reflecting on our memories of Oberlin (and of Penn State where he went as an undergraduate) and on what might help college students, faculty, and administrators move forward in today’s confusing and emotionally-intense cultural environment. My husband and I both now work in higher ed, although in different capacities. He is a professor and I am a museum curator. Colleges and universities are places where the larger questions of power, culture, governance, and social pressure play out in intricate and heavily-scrutinized fashion. They provide packaged case studies for all of the intersecting themes that are of interest to anyone who wants to understand society, or to influence it. They are also places where learning (and learning how to learn) is central to institutional mission. As you’ve noted in this piece and others, faculty have a role to play that goes beyond their subject-matter expertise. But the institution can (and should) support them in their endeavors to set the stage for critical thinking from the first moment a student arrives on campus.

Perhaps a “Social Action 101” training during first year orientation would be beneficial for all students. It could combine a brief history of social movements on campus– with their goals, tactics, and an evaluation of their outcomes– with some generalized advice/guidelines based on the action-reflection cycle you outline above. Oberlin students, in particular, arrive with a great deal of passion, but often with little depth of knowledge about the things they want to change in the world. That’s what college is for! But they are likely to want to act before they’ve spent four (or more) years honing their skills as researchers, evaluators, and actors. They could use a crash course, even if they don’t know yet what they may want to protest, influence, or speak about.

I remember the only time I considered leaving Oberlin prematurely was during spring break my freshman year. The Iraq war had been launched in March 2003, and students were moved to protest. I remember feeling angry and frustrated by the political situation, and joining the walk-out organized by OCAW (http://cdm15963.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/compoundobject/collection/p15963coll9/id/154757/rec/24). The faculty had left it up to individual professors as to whether they would cancel class on March 20, 2003. I can’t recall whether I had to miss class to do it, but I joined a large gathering of students on Tappan Square at noon. I was immediately struck by what felt like a lack of cohesion. In addition to people holding up signs protesting the previous evening’s bombing of Iraq, there were representatives of seemingly unrelated organizations including the 4.20 group protesting in favor of marijuana legalization, a climate change activist group, and Students for a Free Palestine. After milling around for a while, I found myself moving north along Main Street without knowing where the group was headed. When I learned that students were planning to “storm the high school” because they felt it was unjust that the high school students had not bee released to join the protest, I quietly walked back to my dorm. I know that there were teach-ins organized by professors that week (along with organizations without college affiliations), and that some faculty set aside time to talk about the war after spring break, but mostly I felt lonely and confused. It had seemed appropriate to respond to what appeared to be an unjust preemptive attack by the U.S., but the response felt lame and incoherent. The enormous protests held in major cities around the world in February when war was still on the horizon had seemed to yield no power or recognition. And the walk-out in Oberlin felt like a dim echo of what was already doomed to be ignored.

I bring this up to remind myself of what it was like to be a first year in college with strong feelings on current events, surrounded by passionate people, at an institution with a reputation for encouraging people to speak their minds. I didn’t feel then like anyone knew what they were doing, and I thought strongly about going somewhere with a little less passion. I’m glad I stayed. By the time I graduated, I felt like I had gained important skills needed to help me evaluate what to act on, and when to act (although those are perennially difficult questions), but it’s helpful to remember that first and second-year students are usually nowhere near that level of understanding…

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment, Adina. I remember well that particular demonstration and, although I was hardly a first-year student, and had been teaching at Oberlin for about 15 years at that point, I felt very similar about it. A sense of excitement on approaching the bandstand on Tappan Sq, a sense of confusion as the signs were, as you note, all over the place, and a real sense of dismay when the students decided to march to the high school to “liberate” it. It was a sign that our students either didn’t understand the bind they would place the high schoolers in if they left class without permission from their parents (something that the college students didn’t have to worry about), or that they just thought that their approach would naturally be the correct one for all Oberlin residents. There is a certain resonance with the Gibson’s affair in that demonstration. Thanks for reminding me (and our readers) of it.

LikeLike