I returned a few days ago from a trip to the South with my wife and four old friends. We visited important civil rights sites in Birmingham, Montgomery, Selma, Jackson, and Memphis. It was a deeply moving, deeply informative, deeply disturbing, and deeply uplifting trip. There were many highlights, with the Equal Justice Initiative’s museum and lynching memorial in Montgomery among the most moving. Both, in different ways, told the story of the hundreds of years of enslavement and racial terrorism that African Americans have endured in this country. EJI has documented more than 4,000 cases of lynching and underscored that one of the most important motivating factors behind the Great Migration of some 6 million Blacks from the South was the desire to flee racial terror and endemic violence. It is a history that most Americans either don’t know or choose to ignore.

Other sites and museums documented the astonishing efforts of hundreds and thousands of (mostly) unnamed individuals who fought enslavement, Jim Crow, and racial terrorism. In each city, we stopped to read the plaques and remembrances of those who were part of that struggle, soldiers in a battle for equality and dignity. In Montgomery, we read the plaque (left) dedicated to Charles Oscar Harris, African American Community Leader, who was one of the longest active Republicans in Alabama. “On March 11, 1875,” the marker noted, “Harris and other prominent Montgomery African Americans tested the Civil Rights Act of 1875 by purchasing tickets to the white-only section of the Montgomery Theatre. Being denied seats, they pursued their rights in court.” He raised 10 children with his wife, Ellen Hassell Hardaway, 9 of whom attended college (the 10th died in childhood). Mr. Harris, the plaque informed, attended Oberlin College.

Other sites and museums documented the astonishing efforts of hundreds and thousands of (mostly) unnamed individuals who fought enslavement, Jim Crow, and racial terrorism. In each city, we stopped to read the plaques and remembrances of those who were part of that struggle, soldiers in a battle for equality and dignity. In Montgomery, we read the plaque (left) dedicated to Charles Oscar Harris, African American Community Leader, who was one of the longest active Republicans in Alabama. “On March 11, 1875,” the marker noted, “Harris and other prominent Montgomery African Americans tested the Civil Rights Act of 1875 by purchasing tickets to the white-only section of the Montgomery Theatre. Being denied seats, they pursued their rights in court.” He raised 10 children with his wife, Ellen Hassell Hardaway, 9 of whom attended college (the 10th died in childhood). Mr. Harris, the plaque informed, attended Oberlin College.

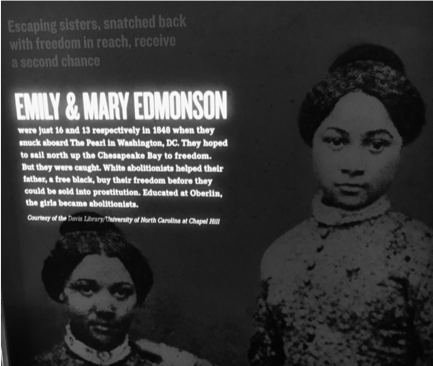

In the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, we learned about Emily & Mary Edmonson (right), who “were just 16 and 13 respectively in 1848 when they snuck aboard The Pearl in Washington DC,” hoping to sail north to freedom. They were caught, but “white abolitionists helped their father, a free black, buy their freedom before they could be sold into prostitution. Educated at Oberlin, the girls became abolitionists.”

In the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, we learned about Emily & Mary Edmonson (right), who “were just 16 and 13 respectively in 1848 when they snuck aboard The Pearl in Washington DC,” hoping to sail north to freedom. They were caught, but “white abolitionists helped their father, a free black, buy their freedom before they could be sold into prostitution. Educated at Oberlin, the girls became abolitionists.”

Walking on, we came on a tribute to Dr. Anna Julia Cooper, “one of the first African American women to earn a bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degree.” Dr. Cooper graduated from Oberlin in 1884.

In Montgomery, we visited the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church where Dr. King served as pastor from 1954-1960. Our tour guide, Wanda Howard Battle, led us to a wall of portraits of the church’s pastors. She pointed to a photograph of Vernon Johns (left), who served immediately prior to Dr. King. Johns graduated from the Oberlin Seminary in 1918.

In Montgomery, we visited the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church where Dr. King served as pastor from 1954-1960. Our tour guide, Wanda Howard Battle, led us to a wall of portraits of the church’s pastors. She pointed to a photograph of Vernon Johns (left), who served immediately prior to Dr. King. Johns graduated from the Oberlin Seminary in 1918.

All this was fresh in my mind as I watched Ted Koppel’s CBS Sunday Morning report on the Oberlin-Gibson’s affair. His segment had all the subtlety of a snowplow in a blizzard. From the first moment to the last, the coverage was geared to tug on the heartstrings of its early morning viewers by foregrounding Dave Gibson’s illness and his elderly father’s broken neck. (I am sincerely sorry for Dave’s, and his family’s, pain and suffering. I have known him for decades and always enjoyed our chatter in his store; I continue to wish them all well.) But neither the elder Gibson’s fall and resultant broken neck – which has never been demonstrated to be linked to the ongoing civil suit – nor Dave’s tragic illness have anything to do with the issues involved in the lawsuit and do not belong in a journalistic account which attempts to shed some light on what happened on November 9, 2016, and in the ensuing days and months. By closing his segment as he did, suggesting that “David Gibson, in the terminal stages of pancreatic cancer, may never know the answer” to the question “What is the fair price for a family’s good name?” Koppel left little doubt as to where his own sympathies lay.

Equally problematic was his roster of on-screen interviewees consisting of individuals who were overwhelmingly sympathetic to the Gibson’s cause. Dave Gibson was given most on-air time, and he was supplemented by conversations with Lee Plakas, the Gibson’s attorney, Misty Smith, a juror who found for the Gibson’s, and Dan O’Brien, a reporter with the Chronicle Telegraph, whose coverage showed a striking support for the plaintiff’s case.

The sole interviewee who could speak on the College’s behalf, President Carmen Ambar, was interrupted (by my count) five times by Koppel whereas the others’ answers to his questions were not only unchallenged, but often prompted. Like a lawyer leading a witness, Koppel asked juror Smith, “You were personally convinced, and the other jurors were convinced, that the college supported the students financially?” “100%” came the unsurprising reply. The camera kept a steady, lengthy gaze on Dave Gibson’s face as he struggled with his emotions when talking about his elderly father. (Nathan Carpenter, editor of the Oberlin Review was on air for 29 seconds but nothing remotely relevant remained in the broadcast.)

Koppel’s report was built around the issue of reputation, i.e., the Gibsons’ reputation, asking more than once, “what price can be put on a family’s reputation?” And this, more than the events themselves, was at the heart of the CBS report. The facts of the case were presented in piecemeal and dramatic fashion, with a scrolling yellow marker on an email highlighting the possible reimbursement of $100 of gloves standing in for the smoking gun which inevitably led jurors to their $44 million verdict against the college. (If the glove fits, you must convict!) Indeed, the only new information in the report (for those of us who have followed it, granted, only a tiny minority of those who tuned in on Sunday morning), was offered by Misty Smith, one of the jurors. She told Koppel that after hearing Dave Gibson’s emotional testimony about how he didn’t want his 91-year old father “to pass away [having] people thinking he was a racist…you just feel the heart [sic], like the whole courtroom just went [phew]. You know, like that, everyone I think was trying to hold back tears.” Juries are won with emotion and narrative, and the plaintiff’s lawyer understood that perfectly. The student protest, labeling the store as racist, and the college’s refusal to affirmatively state that Gibson’s wasn’t racist (something the administration had never said in the first place), was seen as an unwarranted and unprecedented attack on the Gibson’s reputation. [For those who want to place the Gibson’s specific response within a larger analytic framework, I would recommend Robin DiAngelo, White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk about Racism (Beacon Press, 2018).]

Reputation was on Koppel’s mind when he discarded the kid gloves with which he had handled the other interviewees and began a cross-examination of President Ambar. Why does a journalist of Ted Koppel’s reputation not question a single statement by interviewees who support the Gibsons and yet interrupt, dispute (“Factually correct, but still misleading,” he says as an aside to his audience after one of her responses) and challenge the – let’s just come right out and say it — African American president of Oberlin College, someone who wasn’t even at the College when these events happened?

For someone concerned with reputation, it certainly seemed to me that his intent was to undermine her reputation. “I mean,” he asked, “if your reputation was destroyed overnight, you could hardly put a price on that, could you?” Seriously? A classic when-did-you-stop-beating-your-wife question? This was followed by a demand that she “be specific” (i.e., name names) of those who have suffered mistreatment in the store, something he well knows she will not do on national television. Look, I have been at Oberlin for 33 years, long enough to know that charges against the store are raised periodically, long enough to have talked to, and heard of, young black men who were asked to take off their backpacks when entering the store while their white friends weren’t. This information neither proves or disproves the charges the students leveled against the store, for while I am aware of that history, I also enjoyed my daily conversations with the African American gentleman on the register who handed me my daily paper along with his political commentary. Like much else, there is a tremendous amount of complexity involved in this issue, but Koppel (like others) doesn’t seem concerned with that.

For someone concerned with reputation, it certainly seemed to me that his intent was to undermine her reputation. “I mean,” he asked, “if your reputation was destroyed overnight, you could hardly put a price on that, could you?” Seriously? A classic when-did-you-stop-beating-your-wife question? This was followed by a demand that she “be specific” (i.e., name names) of those who have suffered mistreatment in the store, something he well knows she will not do on national television. Look, I have been at Oberlin for 33 years, long enough to know that charges against the store are raised periodically, long enough to have talked to, and heard of, young black men who were asked to take off their backpacks when entering the store while their white friends weren’t. This information neither proves or disproves the charges the students leveled against the store, for while I am aware of that history, I also enjoyed my daily conversations with the African American gentleman on the register who handed me my daily paper along with his political commentary. Like much else, there is a tremendous amount of complexity involved in this issue, but Koppel (like others) doesn’t seem concerned with that.

Reputation. What is the price of one’s reputation? The loss to the Gibson family, Koppel suggested over and over, was more reputational than economic (although, if one is interested in complexity, one should look to the economic issues involved, as well.) But if we are to see the Gibson’s battle as a reputational one, and argue that no one should be falsely charged (a general proposition that I strongly support), then what about the College’s reputation? Since this event, the College’s 186-year reputation as one of the finest liberal arts institutions in the country, one of the best conservatories of music in the world, and, to be sure, an institution that has made its share of mistakes over that long history, has been reduced to this event, and this event only; everything else that it has done and continues to do is viewed through the lens of the Gibson’s affair.

Now, we might expect this reaction from the likes of Michelle Malkin, a right-wing commentator and Oberlin alumna who wrote, “The jury voted. Now it’s time for more parents, alumni and donors of ideological insane asylums like Oberlin to vote with their own feet and pocketbooks. De-fund the divisive defamers of American higher education. It’s the only way they’ll learn.” Less likely, but equally troubling, are the comments (shared by many others) of Richard Epstein, a constitutional lawyer at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, who wrote, “Oberlin College may well go bankrupt, perhaps it should.” Most troubling, to me, are comments by alumni such as one which appeared on social media after the CBS report: “The level of ethical and moral bankruptcy this has demonstrated,” the person commented, “has led me to sever my ties to the school completely…So good luck and go with God as this whole debacle may be the thing that tips the school into closing eventually. I wish I could feel the sorrow I feel at the loss of a place I loved. But my God the way this all played out has left me feeling that the Oberlin of today isn’t worthy of survival.”

[For those who think that the college could have done a better PR job, perhaps that’s the case, but as I wrote in a recent piece about the so-called Bánh-Mi debacle (later picked up by the Chronicle of Higher Education and Vox), in a 24/7 news cycle and feverish social media world, we rarely get to tell our own story – others are telling it for us, and more than often not in a way that reflects neither reality, complexity, or truth.]

And so I ask, in what equation are we asked to feel sympathy for a family that may have been falsely accused by a group of students (and I would highly recommend the analysis by Ciara Torres-Spelliscy, a fellow of the Bennan Center for Justice, on the legal question of boycotts and free speech) and yet applaud the reputational trashing of a nearly 200-year institution, going so far as to call for its closure, because of a single event?

The disquieting irony of the question that Koppel raised to President Ambar – what price can you put on your reputation? – is that while overflowing with sympathy for the Gibson family (and I share in concerns for their health), he nevertheless seemed content to let this incident, which is still playing out in the courts, demolish the reputation of Oberlin College. I remain immensely proud of the College as an important institution of higher education with a proud history and a vibrant present that is played out on a daily basis in the classrooms, labs, recital halls, and art studios on campus. As the editors of the Oberlin Review wrote in the first issue to greet the students as they returned from their summer vacations this year, “even with the media maelstrom swirling, Oberlin students spent the summer doing what they do best: finding work they care about, committing themselves fully to it, and leaving behind a legacy of care and compassion. They again dismantled the notion that this student body is a monolithic entity full of naïve children who know nothing about how to function in the real world. Oberlin students demonstrated — as they have time and time again — that they are fully up to the task of empowering themselves and others to make significant, long-lasting impacts on their communities.”

To answer Ted Koppel’s question: the College’s reputation is invaluable. Take a trip down South, read our history on the monuments, then come and sit in on our classrooms, talk to our Mellon Mays and Bonner Scholars, read the articles that our undergraduates are publishing in national journals, attend a concert, visit the schools where our alumni teach, the research labs where they work, the nonprofits they run. This is why Oberlin’s reputation, no less than the Gibsons’ reputation, should be valued.

I think part of the shock for some of us comes because of Oberlin’s reputation. Before all this, I would never have dreamed some of its students and administrators would have acted so recklessly or that shoplifting by Oberlin students, of all people, would be such a problem, information that has come out since the incident. Oberlin has many things to be proud of. Its conduct here is not among them.

LikeLike

Excellent stuff, as always.

Reputation really is everything to do with it. It’s the only reason the Gibson’s case made it to all the talking heads. A small, family-owned business? The wealthy conservatives would happily crush it under their heels any other day of the week. But it made a useful hammer to bludgeon Oberlin, and by extension, higher education entirely. To them, it’s nothing but a proxy war against the very idea of student activism. I don’t know if they’ll win in their attack on Oberlin, but they won’t win the bigger fight they’ve picked.

LikeLike

Steve: You’re perfectly right about Ted Koppel and his absurd take on the Gibson affair. It was superficial, emotional, one-sided nonsense. More or less standard television, or worse. That said, the College is not without fault in my opinion, and I cannot understand why the trustees and administration did what they did, but perhaps I do not know the whole story. I was a newspaper editor for 45 years, and I know there is always a back story, but this one puzzles me. I am pretty well acquainted with libel law. What you and Koppel are discussing is not the issue, or not in my opinion anyway. As I remember it, libel/defamation is not protected speech. If you defame someone who is not a public figure (Sullivan) you can be sued, and if the jury agrees, you lose. The college claims it didn’t do it, the students did, and that the students are protected by the Second Amendment, and that this case will affect students’ rights to free speech, etc. I don’t agree. The minute the students used college machinery to produce fliers, the minute it authorized the purchase of gloves to warm students’ hands while they defamed Gibson’s, the minute it “supported” the students while they rioted, as it admitted, it shared in the defamation. There would be no case if college officials had not been present at the demonstration because no one bothers to sue college students who don’t have any money. At least that is the way I see it. A lawyer might have another view. If so, I haven’t heard it. The Gibsons, of course, (or their lawyers), can hardly be faulted for seeing a pot of gold and going for it. You have to sell a lot of donuts to equal 40 million dollars, and opportunities like this one don’t come around often. So they went for it, and the jury believed them. I am as heartsick as you are at what this case has done to an institution I have cherished since I landed here in 1942 because it gave me far more than a college education. Moreover, my wife, daughter, and granddaughter are all graduates. The damage that this case has done will be with us all for many years. If you have another take on the case, I would like to hear it.

LikeLike

Hi, Jim. Yes, I do have a different take on it. The very short version rests with the Supreme Court’s 1982 ruling in NAACP v. Claiborne Hardware (See Ciara Torres-Spelliscy, Political Brands (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2019). The longer version will have to wait as I need to pack for a flight tomorrow morning. One small issue – of course you mean the First (not Second) Amendment; one slightly more important issue: you refer to the students who “rioted.” The students maintained peaceful demonstrations at all times. Anyway, more when I return.

LikeLike

I am concerned about the apparent idea that a college should shut down student protests when the merits of the protest are unclear or even wrongheaded. There are entire BDS and anti-abortion movements running out of many college campuses – should the college not let the students meet on campus? Pass out fliers? Take away student financial aid if they start to boycott? In some cases there is actual support for student movements – indeed during the anti-apartheid era, many colleges divested from businesses that they viewed as supporting apartheid. Some colleges are considering divesting from businesses that they believe contribute to climate change. A private college should be able to make that choice and not be sued for naming these businesses from which they pull funds. Oberlin’s supposed support of these student protesters does not differ from what they do for all students – the reality is that the students both as individuals and as groups have access to printers and copiers on almost every campus in this country and they can make whatever leaflets they want about anything they want. We may think the students are wrong about their commitment to BDS or antipathy to Gibsons or Planned Parenthood – but the fact that Oberlin or any college does not try to stop the students is a credit to its own commitment to first amendment principles.

LikeLike

“What’s a reputation worth” is a relevant question, especially for Oberlin College which is facing the same disruptive demographic and market forces as all other small liberal arts colleges.

The way the Trustees, Krislov and Anbar have handled this is gross strategic mismanagement. From a public point of view, this story has been David v. Goliath with Oberlin College being the 800 lb bully in the room. Did the leadership ever consider there was no way they could win the public relations battle? Did they ever consider the impact upon alumni involvement, student recruitment and community support by taking a giant dump on a little five-generation family-owned bakery?

This is even before it went to court. Then we saw all the incriminating emails from Raimondo and others. Honestly, even on the extreme outside chance that the verdict will be reversed on appeal (at best it appears they can only get some slight modification of the award and not have the judgment overturned), any “victory” will be pyrrhic. The financial damage Oberlin has done to its own reputation is going to be far more devastating than the $30-40 million they’ll have to pay the Gibson’s.

And to think, this all could have been avoided 3 years ago if the college had just sat down with the Gibsons and drafted an anodyne statement that the bakery is not a major underground coven for the Klan.

The stupidity is breathtaking

LikeLike

We probably disagree on many points, but the one thing I would challenge is that I don’t think it all would have gone away had Oberlin “drafted an anodyne statement” three years ago. There is reason to think (sorry to adopt the passive voice) that for a number of reasons, this one wasn’t going to “go away.”

LikeLike

I suspect you are right that an anodyne statement wouldn’t have made it all go away, but it would have satisfied the Gibsons and kept the case out of court. Then next battle for Oberlin College would have been within the campus. Any agreement would have sent the students into a frenzy…this was the real fear of the College admins. It’s similar to Japan in 1944-45, where the leaders could see clearly the nation was heading for annihilation – cities burnt to the ground, citizens starving, navy at the bottom of the Pacific – yet could not accept the obvious need to surrender because from the Emporer on down they feared the Army would go wild at the prospect of submission (which a small cadre of junior officers did try an aborted coup).

In many ways, your administration let itself be held hostage out of fear of your students.

LikeLike

Rather an over-blown historical analogy, don’t you think??? I was actually arguing that I don’t think a statement, anodyne or not, would have stopped a law suit. And don’t ask for my evidence since I don’t have any – just a supposition based on “circumstantial “ evidence.

LikeLike

Yea, that comment was overblown. Sorry about that. Wi!l try to be more reasoned n the future. I do at some point want to hear your take about the tensions between students and administration. Having closely followed the cases at Missouri, Evergreen and Yale, I was perplexed by how meekly the admins surrendered to a vocal minority of students. As I try to understand Anbar and the Trustees continuing counter-productive actions, the only motivation I discern is that they fear the student body erupting at any compromise.

LikeLike

See the 2017 history of Washington, DC for many more historic Oberlin alumni/ae. CHOCOLATE CITY: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation’s Capital by Chris Myers Asch and George Derek Musgrove.

LikeLike

Steve Volk, you are a clear thinker and an excellent communicator. However, like the college administration and some Oberlin alumni, you seem unwilling to put yourself in the shoes of the Gibson family and continue to portray the college as the victim. Koppel didn’t put words in President Ambar’s mouth. She opened the racism door – and indicated it was at the core of the discussion – when she could have pushed the colleges argument that they were protecting the rights of the students to speak freely. She was misleading about the gloves when she could have argued that the college approved the purchase out of concern for the safety and well-being of the students.

Have you tried to imagine what it would be like to be unfairly characterized as racist? To have students protest in front of your classroom or office and post flyers calling you a racist with the support of the college administration? To be put on leave without pay for a semester because the college is afraid of how some students might react to your continued presence on campus? I’m not asking these questions to be mean or antagonistic. It just that I’ve read several of your blogs and you seem reluctant to see the situation from the Gibson’s perspective.

I absolutely loved when Koppel asked Ambar what her reputation is worth, not because it put her on the spot and made her look bad, but for the first time I felt that she was actually putting herself in the shoes of the Gibson family and beginning to understand their “different lived experiences.” Koppel succeeded in a task that the jury tried and sadly failed to do when it awarded the huge amount in punitive damages.

I agree with you that including the short life expectancy of the David and Allyn Gibson was included to elicit sympathy from the viewers, but it also made it clear that the lawsuit is about more than money for the Gibsons. They may never see a dime from Oberlin college while they are alive and couldn’t begin to spend thirty million dollars in the short time they have left. In the end, all they are fighting for is their reputation.

LikeLike

Robert – thank you for your kind comments to begin your post, although they are probably undeserved as I obviously didn’t make my case clear enough. I’m going to add two points here that I hope can be the basis of some new ways of thinking about these events. (1) Yes, it is terrible to be called something that one is not. Who would think that it’s not? This is why I characterized Koppel’s question to President Ambar in the way that I did, as a “when did you stop beating your wife” question since we all know the answer to it. At the same time, I must raise an issue that wasn’t going to come up in the courtroom, that a number of people — young black men in town — have raised allegations against Gibson’s for years. This doesn’t prove that they are or are not racists (a truly complex charge – and I’ll recommend Ibram X. Kendi’s latest book as a start), just that the accusations didn’t materialize out of thin air. (2) Yes (a repetition of #1, but stay with me), it is terrible to be called something that one is not. But here I’ll put on my historian’s hat and try to make my point, hopefully without overdoing the historical analogies: African Americans in this country have for centuries been unfairly charged with the most heinous crimes, and not only did they not get a fair hearing, but they were (and continue to be) lynched, jailed, murdered, mistreated, and, above all, disbelieved. These violations remain uncompensated, either monetarily or reputationally. Their stories, now often recorded on police body cams which narrate them after they are dead, are still discarded by juries that continue to acquit police who shoot Black men, women, and boys in cold blood, often seconds after arriving on the scene. So yes, above all, African Americans know what feels like to be “unfairly characterized.” This is a history they carry with them, passed along by African American parents to their young sons before handing them the car keys. And then a white store owner is charged by some students with being a racist, and a jury agrees and awards the family $40+ million, and the media (including Mr. Koppel) finds the damage to the Gibson’s good name to be an outrageous violation. So Koppel rushes out to Oberlin to ask its president (who wasn’t even here when the events happened): Can you imagine what it would be like to be unfairly characterized as…? Yes, she could, of course she could; but Koppel is hardly about to give her the time or space to truly consider what that has meant historically. So, if I have any point at all to make it is that there are histories behind these events that make their understanding more complex then Koppel or most of the media or most who have commented on this case would like. Our legal system is not set up to take context into account; it considers the particular facts of a specific case and makes its determinations (although, as I have suggested, juries don’t drop out of thin air – they carry their own contexts. A Lorain county jury brought a different context to this matter than, say, a Berkeley jury would have). Justice, on the other hand, would demand that we understand history and context. I would hope that when we consider the issue of “reputation,” we take int account not just the “facts of the case,” but the larger historical framework which has made some peoples’ reputation more valuable (both monetarily and in other ways) than others.

LikeLiked by 1 person