When I first began teaching in a tenure track position, my colleagues advised me that I had joined a department with a deep bench of knockout lecturers. One, I was told, could breeze through a detailed 50-minute lecture without once glancing at his notes (which he conspicuously placed on the lectern at the start of each class so as not to unsettle the students). The A-team’s lecturing prowess was reflected in the outstanding teaching evaluations they received (and is still vividly recounted by their 60- and 70-year old former students who return to campus for alumni weekend). If I wanted to garner equally stellar evaluations, it was impressed on me, I would have to step up my lecture game.

Economics Professor William H. Kiekhofer, lecturing in 1940 (Univ. of Wisconsin Archives).

I actually got pretty good at it – not to the level of memorization, but still good enough to boost my evaluations. All good, until it dawned on me that lectures could be inspirational, drawing students into the subject matter, but they weren’t the best way to promote student learning. And even the best lecture didn’t seem to capture the interest of those who purposefully occupied the back rows in my classes. My evaluations, while often good for my ego and, no doubt, helpful in my yearly evaluations, didn’t indicate whether any learning was taking place in class.

Encouraged by some reading in the scholarship of teaching and learning, greatly inspired by colleagues near and far, and (by then) protected by tenure, I moved away from lecturing in an effort to better address student learning. I had changed my classroom practice – but the evaluation process remained remarkably static, still using the same end-of-term questions to measure my effectiveness as a teacher.

Even though these standard student evaluation of teaching (SET) instruments have been broadly critiqued as being subject to racial and gender bias; even though a meta-analysis found little to no correlation between how highly students rate their instructor and how well they have learned the subject; and, even though 18 scholarly associations identified the current use of student evaluations of teaching as “problematic” and called for a more “holistic assessment of teaching effectiveness,” the qualitative end-of-semester SET is still the most widely used measure of teaching quality in higher education.

The most common reactions to the SET regime that I have encountered over the years were dread on the part of untenured instructors and cynicism on the part of tenured faculty. Untenured faculty can spend years mulling over the one or two negative comments in an otherwise positive pool of responses; tenured faculty just shake their heads over the SET’s customer-service orientation and the folly of asking students how they would rate the instructor’s “mastery” over the material. Even those ultimately charged with determining salary, promotion, or the granting of tenure were resigned to the futility of determining teaching quality based on a reading of the candidate’s SETs. At the end of the day, we were told, just look for the outliers, those whose numbers are massively good or truly horrendous; ignore the others.

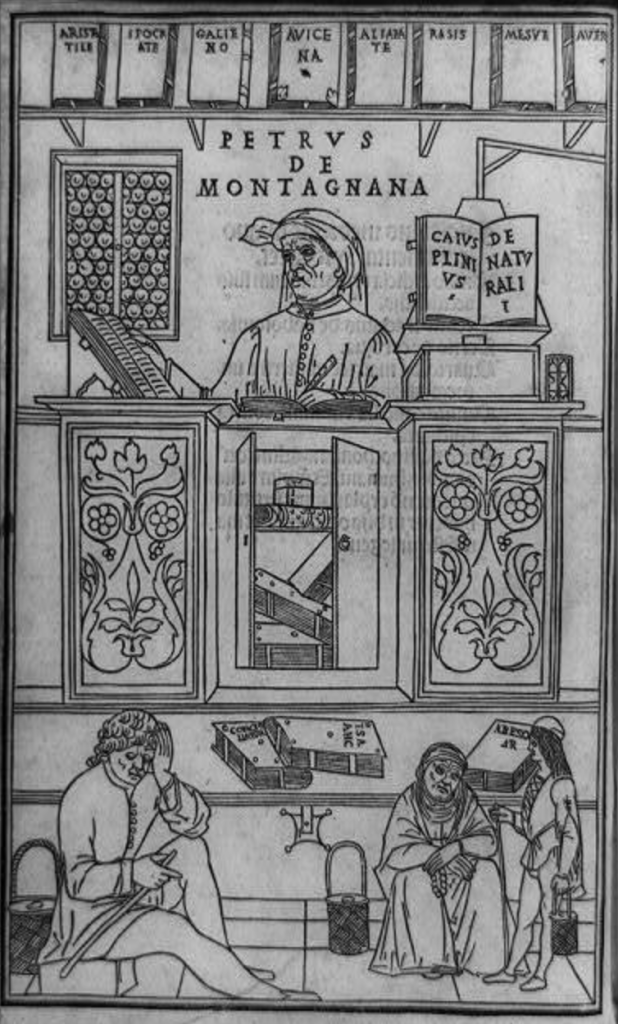

Johannes de Ketham, Fasciculus medicinae (Venice : J. and G. de Gregoriis, de Forlivio), 1495

One certain, and hugely unfortunate, result of this is that many faculty, particularly untenured instructors, know that spending time on improving their teaching (e.g., spending time researching the links between pedagogical approaches and student learning and, on that basis, developing evidence-based teaching practices) doesn’t yield the same rewards as more research and publications. Faculty may be many things, but stupid, we aren’t. As Gabriela Weaver, assistant dean for student-success analytics in the College of Natural Sciences at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst notes, “if something is clearly not being valued or evaluated or rewarded, then [faculty] are going to put their time where they are being rewarded.” It is abundantly clear that the prestige of universities, and increasingly of elite colleges, rests on research output, publications, and grant dollars raised, much more than on teaching effectiveness, so it should be no surprise that faculty incentive to invest in better teaching is, um, quite modest.

It’s not a secret why, then, even at a time when, as Beth McMurtrie pointed out in a recent article for the Chronicle of Higher Education, “A growing body of research shows that effective teaching is hugely influential in determining whether students succeed in college,” and even for colleges which pride themselves as valuing teaching as their primary function, we continue to rely on these problematic instruments to measure the quality of teaching. It’s just easier to do it this way. SETs are easy, cheap, and “give the appearance of objectivity.” And, as we all know, higher education is quite good at fetishizing “objectivity” and “rationality,” as though “the goal of becoming educated is to achieve a Dragnet/Vulcan hybrid world view, ‘just the facts ma’am,’ filtered through a perfectly rational mind.”

Further, if you haven’t noticed, faculty don’t particularly enjoy spending time evaluating each other, at least not when it comes to evaluating each other’s teaching chops.

On top of this is the concern that teaching quality can’t really be measured, at least beyond measuring teaching as performance (“were you engaged by the class?”). How do we measure the impact of faculty teaching on student learning? What about the student who does well on exams because she brings an intrinsic interest in the subject to the class? Or the student who comes into the class already equipped with a strong foundation in the field? Or the student who learned more from his peer study group than from the instructor? How do we get at these aspects of student learning when assessing faculty teaching?

This is what more holistic approaches to teaching and learning are designed to do: approaches that are sensitive to the ways that instructors can help all students develop an intrinsic interest in their subject matter; approaches that recognized faculty who are able to work effectively with students at different knowledge and skill levels; approaches that capture those faculty who facilitate the formation of peer study groups.

Master and Child, from the 1705 English edition of Orbis Sensualium Pictus

Some places are doing just this. McMutrie, for example, lists five universities that are “investing in more thoughtfully designed course evaluations, preparing faculty members to substantively critique their colleagues, and fostering discussions of teaching in departmental meetings, which is often where change happens.”

*Appalachian State University (Teaching Quality Framework)

*Boise State University (Framework for Assessing Teaching Effectiveness)

*Indiana University (Identifying Pathways for Excellence in Teaching)

*The University of Kansas (Benchmarks for Teaching Effectiveness)

*The University of Oregon (Revising Teaching Evaluations)

While each offers a slightly different framework for evaluating teaching quality, they all share some common characteristics. Rather than the single, end-of-semester student evaluation of teaching, they rely on gathering multiple sources of evidence provided at different points throughout the semester. These sources often include whether and how instructors focus on indicators of good teaching that are supported by research on teaching and learning (scholarly teaching, the development of pedagogical expertise, the implementation of evidence-based practice); effective course design (aligning course materials with learning outcomes, adopting backward design techniques); creating inclusive, student-centered learning environments (allowing for diverse perspectives and greater student engagement); and robust reflective practices (demonstrating an instructor’s reflection on feedback from a variety of sources including students, peers, and self-reflection).

To be sure: this implies considerably more work than handing out an end-of-semester SET or being visited by a department colleague once or twice before the tenure decision. But it’s worth it if what we’re looking for in teaching evaluation is not “your overall rating was 4.2 out of 5,” but feedback that can help all instructors think about how their teaching relates to student learning in a process of continuous improvement.

If you’re interested in pursuing this further, a number of coalitions and consortia have joined efforts to transform the way teaching is evaluated at colleges and universities. Among them are the Bay View Alliance, a network of ten research universities in the US and Canada, and TEval, formed in 2017 by four public research universities to explore a more holistic approach to documenting, recognizing, and rewarding high-quality teaching.