For many summers over more than a decade, I have had the pleasure of working with high school students attending the Great Books Summer Program. Great Books is a program for middle and high school students, devoted to an inquiry-based pedagogical model. Students engage in deep discussions of a set of texts selected by the instructor to guide them through a topic, subject or problem of our own design. Last year, for example, I taught two courses at the program’s Stanford campus: “From Harm to Repair” with readings ranging from Seneca and Aeschylus to James Baldwin and Desmond Tutu, and “From Law to Justice” in which we discussed works by Whitman, Camus, Ha Jin, Shakespeare, and Frederick Douglass, among others.

This year, I am inaugurating the program’s Scottish venue at the University of Edinburgh. I struggled for a bit wondering how to merge the Highlands locale with my ongoing concern for the truly frightening moment we face in the United States. I have given many “Know Your Rights” presentations since mid-January, and each one seems to require more information as Constitutional Amendments fall like so many novice ice-skaters, not simply ignored, but ridiculed by the government. Even if the freedoms and liberties boldly proclaimed in the Declaration of Independence and later enumerated in the U.S. Constitution are, for many, more accurately described in the words of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr as “promissory notes,”, that is all the more reason to defend and extend them with all our strength and imagination.

As a Latin American historian, I found hardly any time to devote to the study of my own country’s history, and what little I once knew about colonial America and the early republic has long since retired, as the poet Billy Collins delightfully wrote, “to the southern hemisphere of the brain/to a little fishing village where there are no phones.” I’ve tried to remedy this in my retirement years, attempting grapple with first century of the nation’s history and to understand, among much else, what Jefferson and the “founders” understood when they wrote of “self-evident” truths, or “unalienable Rights,” or the “pursuit of Happiness.”

It wasn’t long before I came upon a host of Scottish Enlightenment thinkers (Francis Hutcheson, Adam Ferguson, Adam Smith, David Hume, among others) whose ideas were important to, and perhaps shaped, how Jefferson and other early republican thinkers imagined the country they were writing into existence. And so, my course emerged: We would discuss the impact of the Scottish Enlightenment on the ideas expressed in the Declaration of Independence. (I should clarify that it’s way above my pay grade to engage in the hotly debated question of whether one can credit these Scottish philosophers as the “hidden authors” of the Declaration. I’m much more interested in exploring with my students what they meant when they wrote of “happiness” or “Nature’s God” while examining the tensions they acknowledged between individual and communitarian freedoms.)

This long-winded introduction brings me to my main point: the Declaration of Independence itself. You probably haven’t read it lately – I certainly hadn’t until I picked up Danielle Allen’s intriguing, Our Declaration: A Reading of the Declaration of Independence in Defense of Equality (W.W. Norton, 2014). I was most familiar with the Declaration’s two introductory paragraphs, one short and one long, in which the framers set out a number of historically staggering propositions, promises – as I noted – that we are still pursuing; claims that…

* we are all created equal,

* we enjoy “certain unalienable rights,” and

* it is the “Right of the People” to rebel when “any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends.”

As I said, much of my upcoming course will be spent discussing the meaning of these claims.

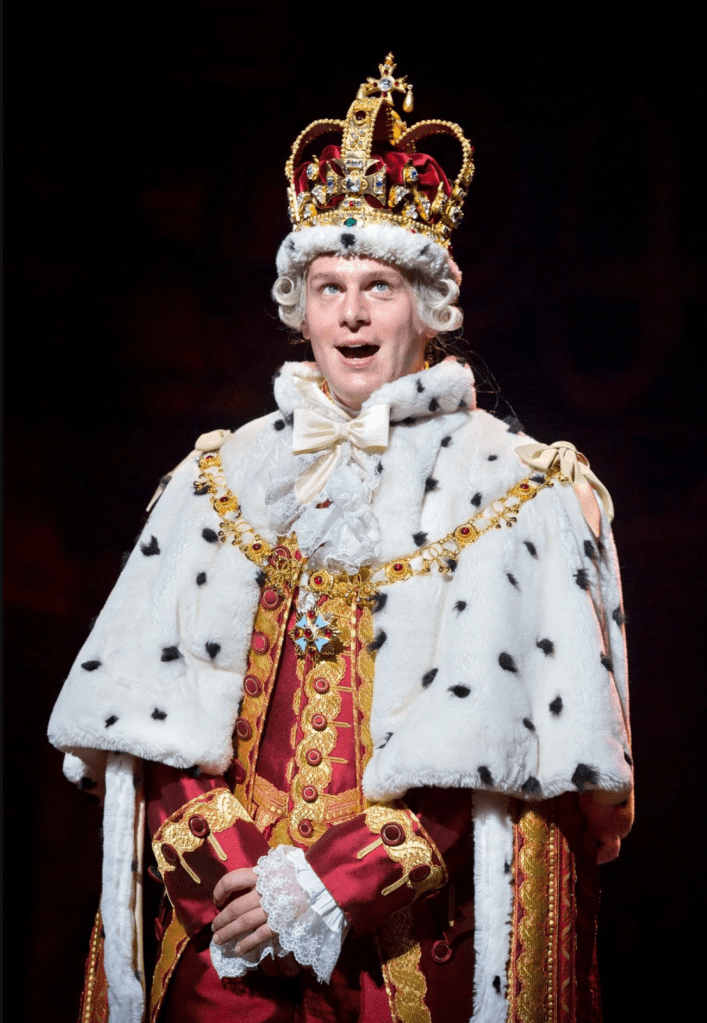

But, until recently, I’ve not spent much time pouring through the bulk of the Declaration, the “bill of particulars,” the charges that the framers leveled against the King, the “proof” that they would “submit to a candid world” to back up their case that, in this particular course of human events, the time had come for revolution.

Now, I’m reminded of the brilliant historian Sterling Stuckey who admonished his students that history needs to be more than an exercise of writing one’s politics back in time; its creative potential is so much greater. And yet, reading through the Declaration’s myriad charges against the 18th century King, and with the prospect of an expected 2,000 or so “No Kings” demonstrations dancing in my head, I could not resist offering, in the original language, an abridged list of particulars taken from that original set of indictments. If my selection of specific “counts” and my strategic use of ellipses are evidence of bias, you have a fair complaint. But neither am I making any of this up. Check out the document yourselves at the National Archives website – unless, following Trump’s hostile takeover of the institution, it has since been disappeared.

The history of the present King … is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.

He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good.

He has endeavoured to prevent the population [note: read as a verb] of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither…

He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone…

He has … sent hither swarms of Officers to harrass our people, and eat out their substance.

He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures.

He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil power.

For protecting [troops] … from punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States:

For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world:

For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent:

For depriving us in many cases, of the benefits of Trial by Jury:

For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offences

For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws, and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments:

He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us.

He has … destroyed the lives of our people.

He is at this time transporting large Armies … to compleat the works of death, desolation and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty & perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized nation.

He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us..

In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.

Wishing Ye All a Very Successful No Kings Day!

Astonishingly relevant on this day. Thank you for bringing us back to the Declaration, Steve. Wishing all a safe and successful No Kings Day!

LikeLiked by 1 person