Retirement offers many opportunities: sleeping later in the mornings (haven’t figured that one out); learning to paint (not really interested); becoming fluent in a new language (没有); streaming more television (Yes!). But in large part, being away from the daily demands of teaching has open the possibility of reading more deeply in fields of history that were outside my own.

U.S. history has been at the top of that list, particularly the early republic, slavery, Black history, and Black struggles for equality and dignity. Ever since reading the 1619 Project a few years ago, I’ve tried to engage the historiographic debate about the shaping of the Constitution: was it “abolitionist” or “pro-slavery”? Sean Wilentz’s 2015 op-ed in the New York Times and David Waldstreicher’s response in The Atlantic nudged the debate over to non-specialists as well, and I followed the rolling, often heated, discussion in the pages of the New York Review of Books (see, for example, here and here), among other publications. That conversation, and a recent review by David Blight in the NYRB, encouraged me to pick up James Oakes’ The Crooked Path to Abolition: Abraham Lincoln and the Antislavery Constitution (Norton 2021).

Reading The Crooked Path led me to reflect, once again, on how historians think about contentious issues in the histories we explore. In the first place, I understand that I have not read deeply enough in the field to draw strong conclusions of my own on the central issue of whether the U.S. Constitution was “pro” or “anti” slavery, although I’m persuaded by Oakes’ superb book that it was both. Second, I found it affirming and energizing that historians who have been deeply immersed in the subject are not just capable of, but willing to modify their analysis in the face of more reasoned arguments and new evidence. As Blight observed: “We may be dead certain, or even mildly sure, about facts and the stories we tell about them, but our craft requires us to remain open to new persuasions, new truths.” Finally, and because of both points, I find it utterly infuriating that these rich debates will be shut out of classrooms in dozens of states because their instructors, quite simply, are forbidden by state law from raising them. Under the banner of opposing the “indoctrination” of students, hundreds of bills have been introduced to ensure that students will be prevented from grappling with the debates that shaped the nation’s history and continue to influence its evolution.

[Thomas Nast, “Emancipation,” King & Baird, Printers (1865), Library of Congress]

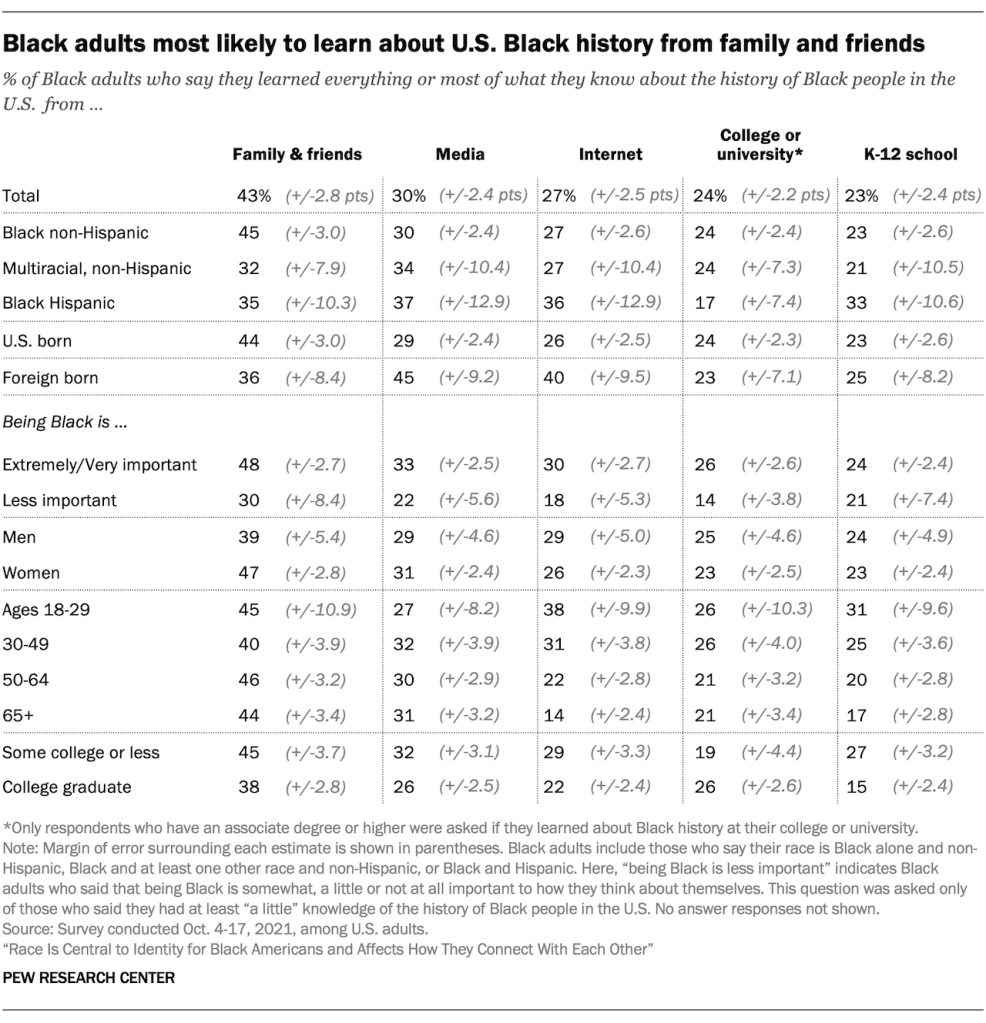

A recent report from UCLA Law found that lawmakers introduced 563 measures against the teaching of “critical race theory” in 2021 and 2022 (more followed this year), with 241 of them having been adopted. What does this mean? I hardly need to repeat what you certainly must be familiar with, but here’s North Dakota’s version: Racism, if discussed at all, must be understood as “the product of learned individual bias or prejudice.” Teachers are prohibited from arguing that it is “systemically embedded in American society and the American legal system to facilitate racial inequality.” Again, I don’t have to tell you the kind of damage these state laws create for teachers who are trying to teach U.S. history with the seriousness it requires, or to students who will be deprived of an honest reckoning with the country’s past or with their own histories. And it’s not as if these new laws will staunch a flourishing curriculum about the history of slavery or Black history in our nation’s schools or universities. According to a Pew Research Center Report for 2022, less than a quarter of Black adults reported learning about U.S. Black history from K-12 schools, colleges, or universities. Many more learn about it – about their own history – from family and friends.

Still, seeing that teachers are becoming more eager to use available resources to introduce these necessarily challenging lessons to their students, and understanding that more students are demanding the knowledge that will help them navigate the deep divisions in U.S. society, Republican legislators have decided that this should not happen. They, not teachers, will dictate how history must be taught. The debate about slavery and abolition in the U.S. Constitution has produced a remarkable, often fraught, and truly meaningful attempt to deal with the U.S. past. If these legislators get their way, students will be unable to engage that debate because one side has been locked outside the schoolroom doors. There will be no debate – only indoctrination.

Fortunately, there are resources that exist, organizations that can help, and teachers and students who refuse to be intimidated or deprived of the education that is their right. For post-secondary history teaching, I would recommend the American Historical Association’s “Teaching History with Integrity” project and the resources it offers. The AAUP (American Association of University Professors) offers abundant resources and actions designed to counteract political interference in higher education. For K-12 education, NCTE (National Council of Teachers of English) provides resources at all levels from early-childhood to college. (See, for example, their statement: “There Is No Apolitical Classroom: Resources for Teaching in These Times.”) For resources to help fight censorship and the banning of books, the American Library Association provides multiple resources and approaches. Silence, masquerading as “neutrality,” is no longer an option if we are to be true to our profession, our colleagues, and our students.