On April 5, I gave a talk at the annual SEPA (Santa Elena Accompaniment Project) dinner in Oberlin. My talk was both inspired by the sermons of Rabbi Sharon Brous, the senior rabbi of IKAR, a nondenominational congregation in Los Angeles that my wife, daughter and I belong to, and “borrowed” in parts from her remarkable book, The Amen Effect: Ancient Wisdom to Mend Our Broken Hearts and World.

Some years ago, after ICE agents carted off five workers in a raid on a local Mexican restaurant, an Oberlin College student, a neighbor active in the Salvation Army, and I collaborated on writing a resolution to bring to City Council. Its intention was to establish as city policy a measure that would prevent police, fire, EMS, or any other city service from asking for the citizenship status of any person who required assistance. The proposed resolution would also prohibit city police from requesting training to prepare them to act as immigration enforcers – something known as 287(g) training. We discussed the matter with city officials and the police but, as a formal resolution, we needed the positive vote of city council. This meant bringing it up for the traditional three readings at City Council before a final vote was taken. Before the first reading, the session where we would introduce it for discussion, so many threats were phoned into the city – threats to me would come later — that the city installed a metal detector for the first time to check those entering the building. I presented the resolution, and it ultimately would pass and be implemented. That resolution, with a few updates since its initial 2008 introduction, is still in effect.

Anyway, sometime after that, I received an angry email from a sender whose name I didn’t recognize. The emailer said she was from Painesville and had driven all the way to Oberlin to express her fierce opposition to the resolution at that first City Council meeting – even though they measure had nothing to do with Painesville. She wrote me incensed that at the meeting,I had accused her of being a “bigamist.” I found that strange, since I didn’t know her and hadn’t the slightest clue (nor any concern) as to whether or not she was a “bigamist.” I soon realized she probably meant to say “bigot,” not “bigamist,” and it was indeed quite possible that I referred to those opposed to the resolution we were introducing as “bigots.”

In any case, since I was leaving in a few days for a semester of teaching in London, I wouldn’t have time to drive out to Painesville to put things right. So I wrote her back suggesting that we talk at least by phone. She agreed, and we spoke a few days later.

I’m not sure I had fully thought out what I was going to say or whether I had an objective in mind when I invited her into a conversation. I’m not even certain why I thought it was important to speak with her. I had no expectation of getting her to change her mind about immigrants, and I didn’t think the conversation would move me to change my mind. I suppose I was just curious to see whether there were points on which we could agree; whether we could find some ground we both could occupy. Certainly, in my mind, there were limits: If she didn’t agree that immigrants were humans, I decided, the conversation would end. As much as we need to be open to one another, as much as we should strive to find the humanity in our opponents, sometimes it’s wrong to pretend that all adversaries are righteous – we need to be clear, now more than ever, that sometimes there aren’t “fine people on both sides.”

So I began the conversation where I often did, attempting to open the path of empathy. “Imagine,” I suggested to her, “that you are in Mexico. You’re a mother trying your best to defend your family, feed your children, keep them away from the gangs that have been popping up like mushrooms in your neighborhood. Your greatest concern, your only concern, is to keep your children safe and free from harm.” Empathy – the “we’re all the same as parents regardless of where we live” appeal, was, after all, my best shot – my best argument. But… nope – no agreement. “Doesn’t matter,” she answered. “That’s not a reason why they should come here. That’s not my problem.”

I moved on: the commandment to care for the stranger is mentioned more times than any other commandment in the Bible — more even than the commandment to love God. Shouldn’t we see immigrants with those instructions in mind? Aren’t we all God’s children regardless of which side of an arbitrary border line one lives on? Maybe this faith-based approach would produce some agreement, some common ground. Nope. As the hours literally went by, I was beginning to despair that we would ever reach a point of consensus.

Because I had run out of other possibilities, I asked her about herself and her family. Since we were talking about immigration and since everyone but Native Americans were at one point to immigrants to this country, I asked her how long her family had been in Ohio. For over a century, she replied. “I’m going to assume that they were farmers, and lived on their own land?” I asked. “Yes.” “Does your family still own that land?” “No.” She said her grandparents had to sell the family farm quite a while ago. “That must have been very hard for them,” I suggested, and she said it was really difficult when they had to move off the family farm. The land had been in their family since the late 1800s. And so I asked: “Why do you think a family from southern Mexico, a family that probably had been growing corn on the same plot of land for literally hundreds if not thousands of years, would just up and walk away from their land, facing the hardships of traveling north, entering a country where they didn’t speak the language or know anyone… just so they could wash dishes in a restaurant in Oberlin?” And, for the first time, she paused. For the first time, she didn’t have an answer. She hadn’t thought about that. And with that, we ended the conversation – with doubt, not certainty. This uncertainty, not having answers to every question but feeling the question was in itself important, was the little piece of turf that we both could inhabit.

Communication and Community

In every encounter, the Rev. Ed Bacon once said, we can be a victim, a hero, or a learner. I certainly wasn’t a hero (or a victim) in that conversation: I can only hope that both of us were learners. So what, after all, was learned? Maybe a very old lesson that we used to know, but seem to have forgotten: the importance of communication; the vitality of conversation.

It doesn’t take long in the book of Genesis, it’s only 4 chapters in after all, before the first murder takes place. Cain kills Abel. Why? Clergy and theologians have offered hundreds of explanations. But, for Elie Wiesel, the answer is right there, literally, in the text. The Hebrew reads, simply: vai-yomer kayn… [ … וַיֹּ֤אמֶר יְהֹוָה֙ אֶל־קַ֔יִן ] “Cain said to his brother…” Dot, dot, dot. It, literally, doesn’t say what Cain said. It’s not that some text had been removed. We are to understand that where we were looking for explanation, something that could tell us why Cain would murder his own brother, there is nothing. “There was no communication,” Wiesel wrote, “and that was the problem. When language fails, when there is no communication, the result is violence.”

Hannah Arendt understood this as well. “Terror,” she observed, “can rule absolutely only over [people] who are isolated against each other…therefore, one of the primary concerns of all tyrannical governments is to bring this isolation about. Isolation may be the beginning of terror; [and] it certainly is its most fertile ground. [But] it always is its result.”

That we live in a moment of terror, I am so sorry to say, is desperately, distressingly clear. Still, I’m not here tonight to talk to you about the horrors that we face at this moment, about the cruelty of an administration that would take away 148,000 pounds of food from a local food bank or one billion dollars from food banks programs all across the United States. It will do nothing but get us further riled up to talk about how the government is now using practices that were first perfected in Chile and Argentina in the 1970s. In the last few weeks we have witnessed plainclothes ICE agents literally abducting students and scholars as they walk down street, handcuffing them and hustling them into unmarked cars, laughing at due process laws, thumbing their noses at the First Amendment. We now live in a country where the President’s political opponents are “disappeared.” I’ll let someone in better control of their blood pressure than I am relate the degeneracy of a situation in which the world’s richest man can dispatch a bunch of 20-year-old bros to wipe out the jobs and livelihoods of thousands of hard-working people, while condemning millions abroad to death by snatching away their medications and food.

I will leave it for someone with a stronger stomach than mine to dwell on the depravity of those who think that it is reasonable – in any stretch of the imagination — to have Kristi Noem, the Secretary of Homeland Security, pose for a photo in El Salvador in front of cage filled with shaved-headed, almost naked male prisoners while flaunting her perfectly coiffed hair, baseball cap, tight-fitting white shirt and a $50,000 Rolex watch, in order to warn immigrants in the United States that this will be their punishment for the crime of being…immigrants.

What immediately came to mind when I first saw that quite highly crafted photograph, was the image of a Nazi official standing in front of the infamous “Work Will Set You Free” entrance gates at Auschwitz, warning Jews, Communists and Queers that this would be their fate. Have we become so desensitized to this government’s outrages that we just accept this?

OK – that’s out of my system. I’m now going to take the very good advice of Chilean poet Pablo Neruda who wrote, “Now we will count to twelve/and we will all keep still/for once on the face of the earth/let’s not speak in [that] language.”

“Life is a hard battle,” Sojourner Truth once remarked. “If we laugh and sing a little as we fight the good fight of freedom, it makes it all go easier. I will not,” she continued, “allow my life’s light to be determined by the darkness around me.” Let’s not, either!

Darkness Gives Way to Light: The Power of Empathy

A week from tonight, many Jews will sit down with family and friends for the first Passover seder. We will remember and relive the story of the Israelite people’s liberation from bondage in Egypt. The “Ten Plagues” is one part of that story – we spill a drop of wine as we recite each plague, a reminder that we are to recall, but not celebrate, the suffering of others. God unleashed ten punishments, ten plagues, on the Egyptians in an attempt to break the Pharaoh’s will, to move him to release the Israelite slaves from their bondage. Each plague was worse than the previous one, with the last being the death of the Egyptians’ first-born children. But it’s the ninth plague that I want to talk about tonight. The next-to-the-last, and therefore next-to-the-worst, plague was darkness: three full days of an impenetrable darkness so dense that “no person could see another.” But why Is this particular plague worse than, say, the waters of the Nile, the source of so much of their food, turning into blood? Three days without light? We could survive that. But boils? lice?

A 19th century Polish rabbi wrote that “The deepest darkness is when one cannot even see his neighbor and therefore can’t join him in his suffering and pain. Once,” he continued, “a person no longer feels his neighbor’s pain, it renders him completely impotent.” This next-to-the-worst plague, essentially, involved the loss of empathy.

We stand at a moment when our ability to talk to each other, to see each other is being contested in a manner it hasn’t been in a very long time. It is astonishing, but not, I suppose, surprising, that we are witnessing an attack on the very idea of empathy, with some happily attacking the notion that there is any benefit to be gained from understanding how others might feel, to be concerned for how others are doing. In February, Joe Rigney a right-wing theologian, published a book titled, “The Sin of Empathy.” Last year, a far-right podcaster, Allie Beth Stuckey, came out with a best-selling book called “Toxic Empathy.” On the “Stronger Men Nation” podcast, the host, Josh McPherson, argued that “Empathy almost needs to be struck from the Christian vocabulary,” a sentiment agreed to by two pastors who joined him on the program. Just a few days ago, on “The Joe Rogan Experience,” our co-president, Elon Musk argued that “the fundamental weakness of Western civilization is empathy.”

I hope I’m not wrong in observing that such sentiments are completely at odds with most faith traditions. There can’t be “authentic dialogue,” Pope Francis has said, “unless we are capable of opening our minds and hearts, in empathy and sincere receptivity, to those with whom we speak.” The medieval Jewish commentator known as Ramban talks about how the young Moses saw the suffering of his people in Egypt. “He directed his eyes and his heart toward them,” he writes, to “know” what his people were experiencing; he used his heart to “feel their pain.”

How, then, do we come together in “empathy and sincere receptivity?” What can bring us to be in community with one another? In her recent book, The Amen Effect, Rabbi Sharon Brous, my family’s LA rabbi from whom I’m plagiarizing huge chunks of this talk, years ago came across a Rabbinic teaching from a 3rd century Jewish legal text: It speaks of an ancient pilgrimage ritual, when hundreds of thousands of people would ascend to the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, the focal point of Jewish religious and political life in the ancient world. The crowd would enter the Courtyard in a mass of humanity, turning to the right and then circling, counterclockwise, around the enormous complex, until they exited close to point where they had entered.

But for someone who was suffering, grieving, for the lonely, the sick – for those to whom something awful had happened – those people would enter the same Courtyard but circle in the opposite direction from the great mass of pilgrims; every step they took would be against the current of the majority. But every person who passed the brokenhearted would stop and ask, “Ma lakh”: “What has happened to you?” Those who walked from right to left would look into the eyes of the ill, the bereft, and the bereaved, and say “May God comfort you.” “May you be wrapped in the embrace of this community.”

The central aspect of this ritual, the central ingredient of community, is the sacred act of not looking away. It is being able to ask: What has happened to you? By doing so, we are engaging in an act of cultural defiance, shifting our mental outlook from encountering a stranger in his or her pain to meeting a sibling, a brother or sister, a friend, a colleague, who needs to be cared for and recognized. We change from passing an “other” whom we would rather not recognize, to finding someone who, like us, was created in God’s image and therefore possesses innate dignity, who is worthy of love in any and every way.

“When we don’t wonder what the other is thinking or feeling, or where the pain comes from, when we don’t interrogate our presuppositions – Rabbi Brous writes – our hearts close to one another.” Our challenge, then, is to imagine ourselves as part of that ritual, to imagine ourselves in a fundamentally different reality, in a world in which we recognize and fight for each other’s dignity.

“Once,” Pope Francis recounted, “I listened to a person for 10 minutes, without saying anything. And at the end, this person told me: ‘Thank you…for your help and your good advice.” But the Pope had said nothing. When a person feels truly welcomed, listened to, esteemed and loved unconditionally – the Pope reasoned – they begin to find solutions to their problems on their own.

Hillel’s Questions

We who hold a dream of building a different kind of society must begin by building a different kind of community. What spirit and strategy must we cultivate to respond to the crisis that confronts us, the darkness that is all around us? As with my conversation with the woman who questioned my concern for the immigrant, I don’t really have an answer to this question, but I do have an orientation to this problem, and it is contained in three questions that Rabbi Hillel posed 2000 years ago.

“If I am not for myself, who will be for me?” That was Hillel’s first question, and, at first glance, it seems to be egotistical, individualistic, even narcissistic. But let’s examine the question: Abraham Joshua Heschel was a prophetic philosopher and theologian. He escaped from Nazi Germany in 1940 and landed in the US where he taught at the Jewish Theological Seminary until his death in 1972. Heschel observed that the chief characteristic of existing as a human is not the “being human” but in what we do with the being we are given. “The most important human experience,” he wrote, “is the recognition that something is asked of us.” Our question, then, is always: “How am I uniquely able to meet this moment?” To be for yourself, then, is to confront what is being asked of us and how we can respond. It means that if we are to live, or to lead, with integrity, we need to have clarity about our own values, resources, interests, and aspirations, as Marshall Ganz, an inspirational organizer, once put it. It means that before we can be “fully present to others, we need to be fully present to ourselves.”

Hillel’s second question is: “When I am for myself alone, what am I?” The ancient pilgrimage to the Temple Mount suggests not only the power of community, of showing up for others, but the absolute necessity of being in community. “All [of us] are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality,” the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr, wrote. We are “tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. I can never be what I ought to be until you are what you ought to be, and you can never be what you ought to be until I am what I ought to be.” Heschel stressed the same point: we are not sufficient to ourselves; life is not meaningful to us unless it is serving an end beyond itself, unless it is of value to others.

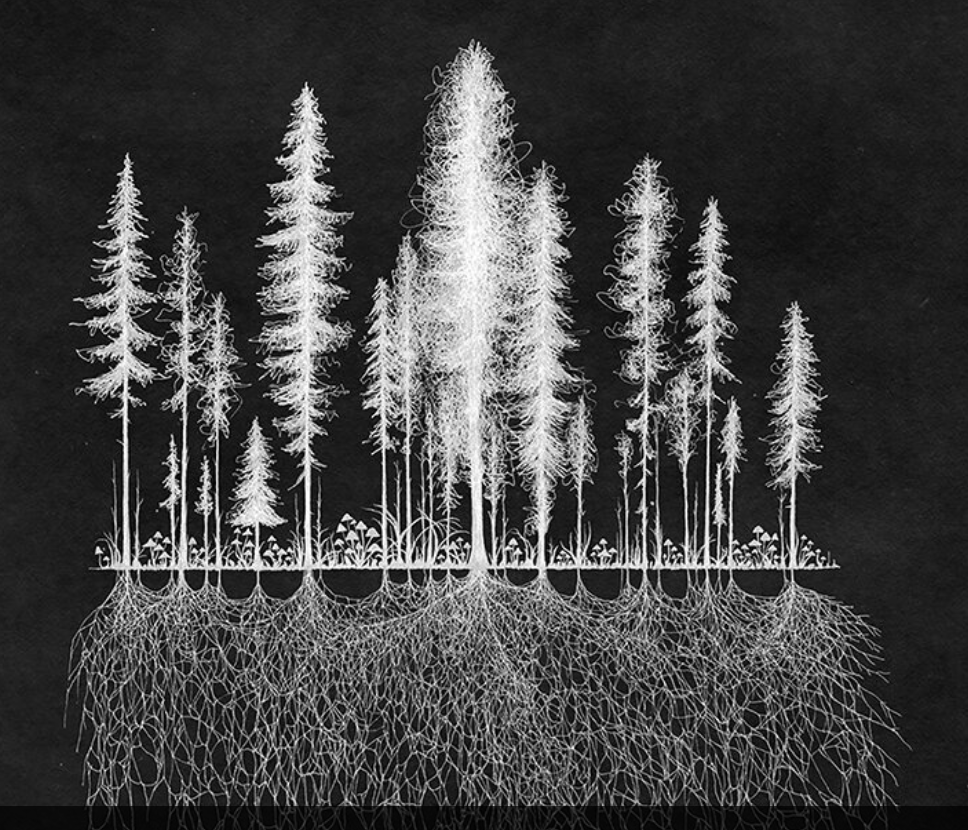

Nor are we the only living creatures for whom this is true. In The Hidden Life of Trees, Peter Wohlleben writes of the expansive networks that tie trees to each other, the underground network of fungi which forms a “wood-wide web” in which trees share water, nutrients and signals. When one tree falls, the whole colony feels the reverberations, even hundreds of miles away. And the root system compensates for the loss of one tree by birthing another. (Maybe this is why the government just cancelled a program aimed at planting trees in poorer neighborhoods, trees which would have made the community cooler, more pleasant, and healthier.)

“I believe that America does best when it is one community standing up for, protecting and in solidarity with another.” So said Sammy after she heard Trump and JD Vance attacking the Haitian community in Springfield, Ohio. So she hopped on her motorcycle and drove the 176 miles from Cleveland to Springfield. She pulled into the parking lot of the Haitian Community Help and Support Center without knowing a single person in town but wanting to help protect the people she saw as innocent victims. Significantly, she declared that the trip had “been one of the most American experiences” of her life.

Our capacity to realize our own objectives is inextricably bound to the capacity of others to realize theirs. Relationships of shared purpose are rooted not only in a commitment to one another, but also to a shared dream; relationships of shared purpose inspire a sense of belonging. They remind us that we’re part of, and working toward, something greater than ourselves as individuals.

Community may not be on the mind of John Boakye, who emigrated from Ghana around 8 years ago, but he is a central part of one. He cares for Jean Fuller, 89, and her husband, Dale, as a home health aide. He works for Cambridge Caregivers, part of the 80% of their staff who are foreign born. Boakye and two other caregivers, also from Africa, help the Fuller family manage life, given Jean’s dementia. Dale, her 91-year old husband, said that Boakye has become “sort of a second brain for Jean since hers doesn’t work so well.”

Hillel’s third question is the one I would like to leave you with: If not now, when? he asked. We are facing the most serious challenge of our lifetimes. Our very sense of what it means to be a human in community and in solidarity with others is not just contested but ridiculed. As a country, we are encountering the most serious constitutional crisis since the Civil War. This is a five-alarm fire. So, the question – if not now, when? – should have an easy answer. After all, as Heschel reminded his students “few are guilty, but all are responsible.”

But still…we wait. After all, we wonder, what can we do as individuals? We’re tiny and the problem is enormous. A rabbi writing in the 4th century was asked to give an estimation of how much one person can do to alleviate the suffering of another? His answer was curiously precise: each individual, he wrote, can alleviate one-sixtieth of the person’s pain. Huh? Why? Well, he reasoned, sleep is one-sixtieth the part of death; the joy of the Sabbath is one-sixtieth of the delight of the World to Come. What is true in all cases is that one-sixtieth is significant enough to be noticeable but not enough to transform the nature of things by itself. “The world asks of us/only the strength we have, and we give it,” the poet Jane Hirshfield wrote, “Then it asks more, and we give it.”

Ella Wheeler Wilcox, “The Things That Count”

“Now, dear, it isn’t the bold things,/Great deeds of valour and might,/That count the most in the summing up of life at the end of the day,” the poet Ella Wheeler Wilcox wrote.“But it is the doing of old things,/Small acts that are just and right;/And doing them over and over again, no matter what others say…”

Rev. Otis Moss III tells a story about a moment some years ago when he was a young pastor at Trinity United Church of Christ in Chicago. The church was on the receiving end of dozens of death threats. A seemingly endless stream of callers threatened to bomb the church and said they were going to kill him. Not only was he a new preacher at the time, he was the father of a young daughter.

One night he woke up suddenly after hearing a sound coming from his daughter’s room. He ran to her room in a panic. But what he found, he later wrote, was his “daughter, Makayla, dancing in the darkness, just spinning around saying ‘Look at me, Daddy.’” Moss somewhat crossly reprimanded her: “’Makayla, you need to go to bed. It’s 3 a.m. But she said, ‘No, look at me, Daddy. Look at me.’ And she was spinning, barrettes going back and forth, pigtails going back and forth.”

Rev. Moss continues, “I was getting huffy and puffy wanting her to go to bed, but then God spoke to me. ‘Look at your daughter! She’s dancing in the dark. The darkness is all around her, but it is not in her!’

Makayla reminded him that “weeping may endure for a night, but if you dance long enough joy will come in the morning. It is the job of preachers,” he reminded, “to [send] this word to us in the hardest of times: do not let the darkness find its way in you.”

We may feel like we’re living through a plague of darkness, but even in the cruelest and bitterest of circumstances, we have a choice: We need to choose to show up in all our strength and all our fragility; we need to find our way to one another; to see one another, to celebrate our humanity with one another. We cannot make the darkness disappear by snapping our fingers, but we can assure one another that we’re not alone as we navigate the greatest challenges before us. To paraphrase a famous Rabbinic teaching: “Nobody expects you to do everything, but that doesn’t free you to do nothing.” We are all responsible.

“Lift every voice and sing,” James Weldon Johnson wrote in what has become “The Black National Anthem.” Lift every voice and sing/Till earth and heaven ring, …

Sing a song full of the faith that the dark past has taught us,

Sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us;

Facing the rising sun of our new day begun,

Let us march on till victory is won.

Wow, this is in every way exactly what I needed to read at this moment, Steve. Thank you!!!!!

LikeLike